By Dunia Garcia-Ontiveros, Head of Bibliographic Services at The London Library. Adapted from an article originally written for History Today.

Niccolò Fontana Tartaglia was one of the less fortunate and most cantankerous polymaths of the Italian Renaissance. He was born in 1500 in Brescia, the son of a humble courier who was murdered when Niccolò was only six years old. The Fontana family had always been poor but after the father’s death their situation became desperate. Only six years later Niccolò received the second major blow of his life, this time a literal one. In 1512 his home town of Brescia was sacked by French soldiers and in the ensuing massacre a twelve year old Niccolò was left for dead after receiving horrific sabre wounds to his jaw and palate. Although he survived the attack the severe injuries he received left him with permanent speech difficulties, which earned him the nickname of ‘Tartaglia’ (stutterer). Niccolò could not hide the stammer but he could at least hide his facial scars by simply growing a beard, which he did as soon as he was able. As a destitute and disfigured boy with a stammer Niccolò would probably not have had high aspirations in life had it not been for one crucial fact: when it came to mathematics he was a child prodigy. Despite his terrible misfortunes Niccolò had great self-belief, some say arrogance, and managed to find a patron who paid for him to study in Padua.

By 1516 the teenager was already teaching in Verona but still lived in relative poverty. He later moved to Venice, where he spent most of the rest of his life. He is best known for coming up with one method for resolving cubic equations and for his bitter quarrel with Girolamo Cardano as a result. Cardano, who was also a mathematician, had persuaded Tartaglia to tell him about this method after swearing that he would never reveal it. Soon after, Cardano discovered that another mathematician, Scipione Ferro, had been the first to find a s

olution to the cubic equation and saw no reason why he shouldn’t publish Ferro’s method and the work Cardano himself had done based on Tartaglia’s solution. It is not clear whether Tartaglia wanted to be the one to publish his method or perhaps he was saving it for use in the many mathematical debates he participated, which had served to enhance his reputation. One thing is certain, Tartaglia felt Cardano had betrayed him and was absolutely furious. He never forgave him and never missed an opportunity to heap insults on Cardano. His reputation was further dented when, sensing defeat, he walked out of a mathematical debate against Lodovico Ferrari, Cardano’s pupil.

Tartaglia published Italian translations of the works of Archimedes and Euclid and is also remembered for his work in military science. It is not surprising that after almost being killed as a child by an invading soldier he should devote some of his considerable intellect and ingenuity to designing fortifications and devising formulae to calculate the reach and trajectory of cannonballs and other missiles. What is less well known is that Tartaglia was also interested in marine engineering and salvage.

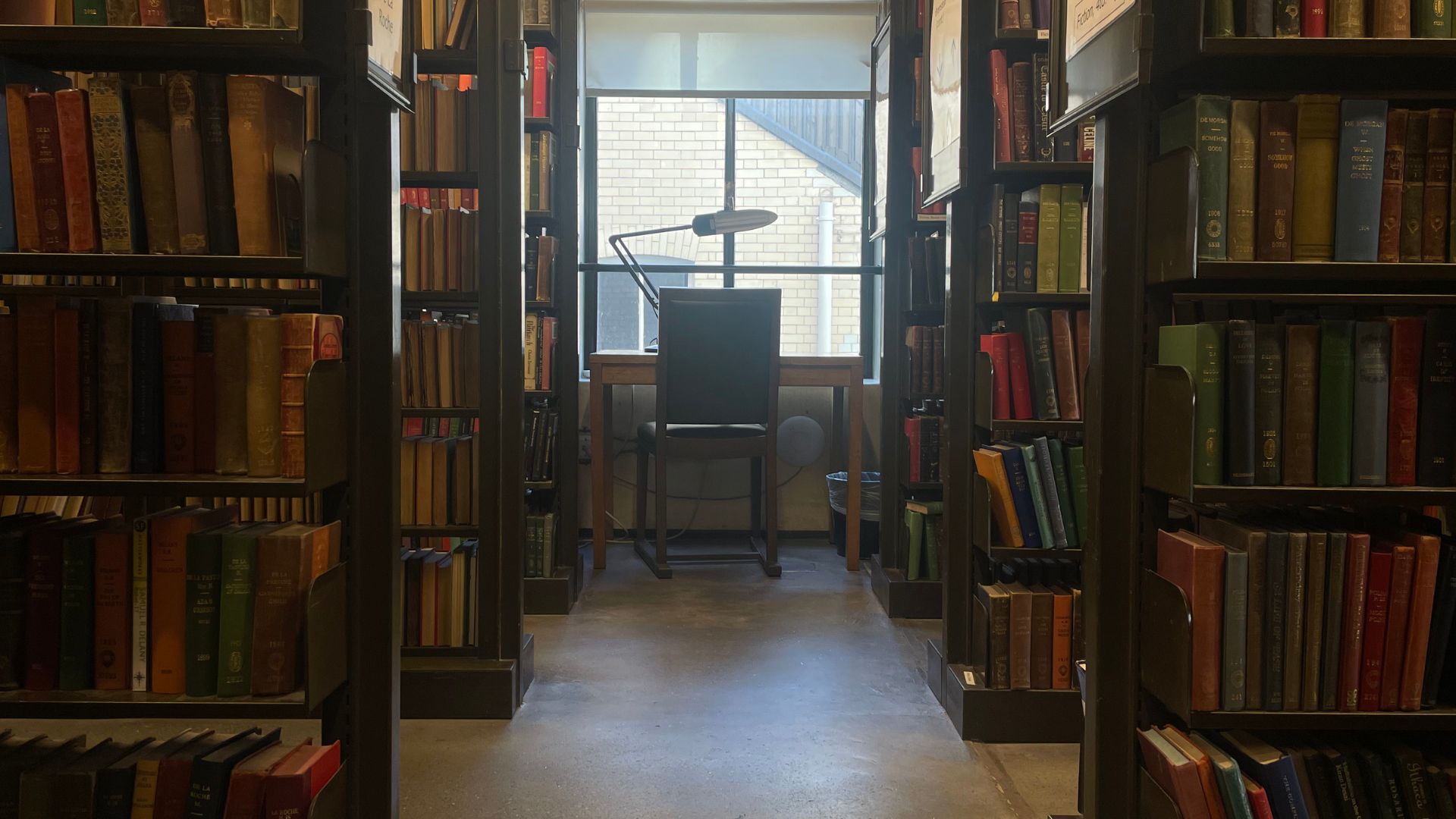

The London Library holds a copy of his work, printed in Venice in 1551, on methods for raising sunken ships, which includes several designs for diving bells: Regola generale da sulevare con ragione e misura nõ solamẽte ogni affondata naue : ma una torre solida di mettallo (General rule for raising not only every sunken ship correctly and with care but also a tower of solid metal).

Despite Tartaglia’s genius and intellectual achievements he never managed to make the social connections that would have secured him lucrative employment and he died in poverty at the age of 51. His life was blighted by tragedy, violence and the highly damaging feud with Cardano.