In this, her third London Library archive blog instalment, Helen O’Neill explores Librarian Robert Harrison’s Commonplace Book and discovers fascinating anecdotes about past ‘literary workers’ in the Library…

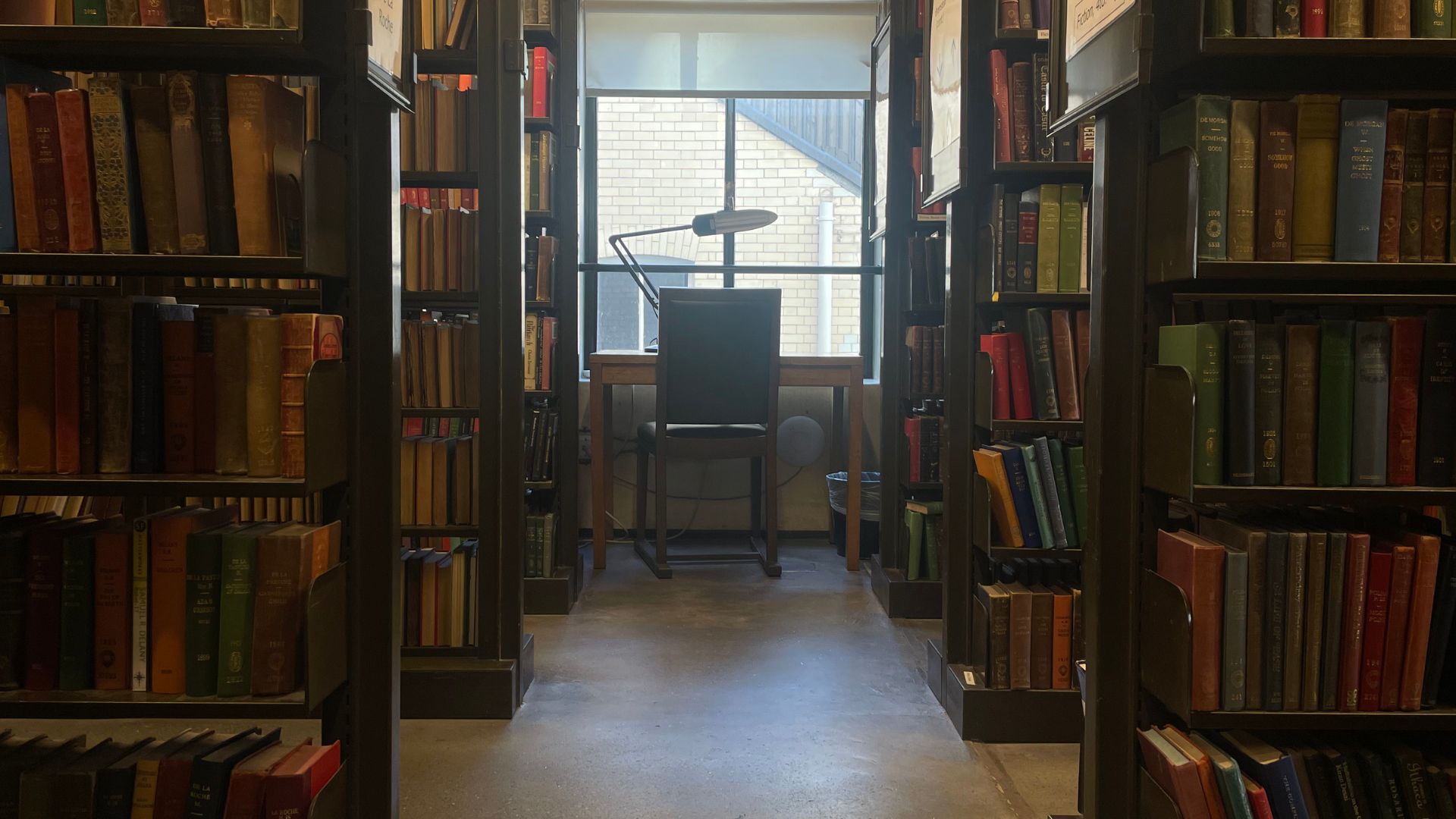

Robert Harrison, Librarian (1857-1893) used this unwanted ledger to scribble anecdotes and personal experiences about his time at the Library. His obituary notice in The Athenaeum in 1897 noted that his “long service at the London Library brought him in constant association with most of the leading literary men of the last forty years”.[1] His entries are dashed off quickly and never re-worked – they brim with social and historical context, but have the immediacy of conversation. His anecdotes pre-date the construction works of 1896-1898 which brought in the Issue Hall, main reading room, grilled Back Stacks and Literature block. During Harrison’s time, the membership would have rubbed shoulders, in what was essentially still a town house being filled with books. The photographs below pre-date the Victorian construction and remodelling works and give a flavour of the Library as it was in Harrison’s day.

I have picked two entries from Harrison’s Commonplace book: George Eliot, is the subject of the first extract, and Alfred Tennyson, (as he was at the time), is the focus of the second. Transcriptions are displayed below the manuscript image.

Are Harrison’s anecdotes just tittle-tattle or do they provide revealing insights into a network of Victorian literary workers making use of the Library during his time? The extracts, though brief and entertaining are insightful. George Eliot was a formidable intellect and freethinker – and in 1859 no-one would have had more first-hand experience of her ability than the dashing Byron look-a-like, John Chapman; and Tennyson did have very real tensions between his inner and outer worlds, and struggled in the limelight.

In these two short snippets Harrison highlights George Eliot, Tennyson, the Irish poet William Allingham, and Dr Chapman, the influential publisher and proprietor of the radical Westminster Review, but it is the context, as well as the content, of Harrison’s anecdotes which make them zing with interest. In addition to the literary movers-and-shakers, Harrison provides us with specific Victorian cultural references points. We get a whiff of phrenology, (in its heyday during this period); and we are whisked off to the Egyptian Halls on Piccadilly (where “sofa stalls for three persons”[4] went for a guinea) to see the illusionist Dr Lynn, “the embodiment of all the strange manifestations and phenomena of the so-called spirit-media”[5] who was enthralling the metropolis every evening at 8pm in 1873, as the Evening Standard reported:

“During the past week an entertainment – one of the most extraordinary ever witnessed by a London audience- has been given nightly at the Egyptian Hall. Dr. Lynn, who is a wizard of the most marvellous skill … comes to us from Paris with a certificate of excellence from no less a person than the poet Victor Hugo…”[6]

I doubt even Victor Hugo’s personal endorsement would have been any comfort to Tennyson but I confess to being hugely interested in the fact that Tennyson, whose work is littered with protagonists in psychological states of suspension, went to Dr Lynn’s show. I am intrigued too by Harrison’s conversation with Chapman, and am rather impressed that in his anecdote George Eliot’s intelligence gets prime billing, ahead of her agreeable conversation, her looks, and her radical life choices.

Harrison used the ledger for what he called his “scrawling”[7] but his anecdotes act rather like flares, illuminating momentarily the hubbub of Library members with whom he came into contact, and the cultural and historical context in which they moved.

If you are interested in reading Harrison’s Commonplace Book it was transcribed and published in The Cornhill Magazine in December 1931 under the title “A Bundle of Dry Leaves” by his grandson Douglas G. Browne. The Cornhill Magazine is available in Periodicals 8vo in the Basement, sadly not through JSTOR.

Next time: Bram Stoker and Henry Irving get in on the act…

© Helen O’Neill

[1] Quoted in Douglas G. Browne, “A Bundle of Dry Leaves” in The Cornhill Magazine December 1931, p. 746.

[2] Robert Harrison, Commonplace book of anecdotes and personal experiences 1857-83

[3] Ibid

[4] Morning Post May 26, 1873, p.1.

[5] Ibid

[6] The Standard May 30, 1873, p. 3.

[7] Quoted in Douglas G. Browne, 1931 p. 746.