Former London Library member Richard Conyngham on seeking refuge from cocker spaniels and finding his own special literary sanctuary at The London Library…

The following article was published in the Summer issue of Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly - 96 pages of lively personal recommendations for books of lasting interest. It’s an eclectic mix, covering all the main categories of fiction and non-fiction, and contributors are an eclectic bunch too! Visit the Slightly Foxed website for a trial issue.

Who are they, I wonder, these elderly gentlemen fast asleep in the red leather armchairs? Retired brigadiers whiling away their autumn years in a room full of books, or eminent scholars dreaming of literary pursuits? That young woman with the windswept hair, foraging in Fiction S–Z, is she a lost and lonely bibliophile or the next Rebecca West? And how can that dandyish fellow in the crimson sports jacket afford to scoff and snort through the periodicals all day?

When the editors of Slightly Foxed first suggested I take my editorial work to the London Library, I confess I knew very little about the place. From afar, it seemed a refuge for posh authors and a pitstop for peersen route to their clubs, not a place for an unkempt youth like me. And yet, at the Slightly Foxed office, the situation was becoming urgent. With the cocker spaniels growing increasingly distracting and the phones always ringing, how was the editorial assistant ever to do his work? The London Library was the obvious solution, but then there was the issue of the membership fee.

In the end, it was a customer at the Slightly Foxed bookshop on Gloucester Road who had the final word. Overhearing my doubts, he leant across a shelf of battered green Penguins and boomed: ‘My boy, at £1.20 a day, it’s a steal. You won’t look back.’ And so it was that two weeks later, on a frosty January morning, I set out for 14 St James’s Square with a list of titles to take out on loan, a catalogue to write, and a newly acquired membership card to guard with my life.

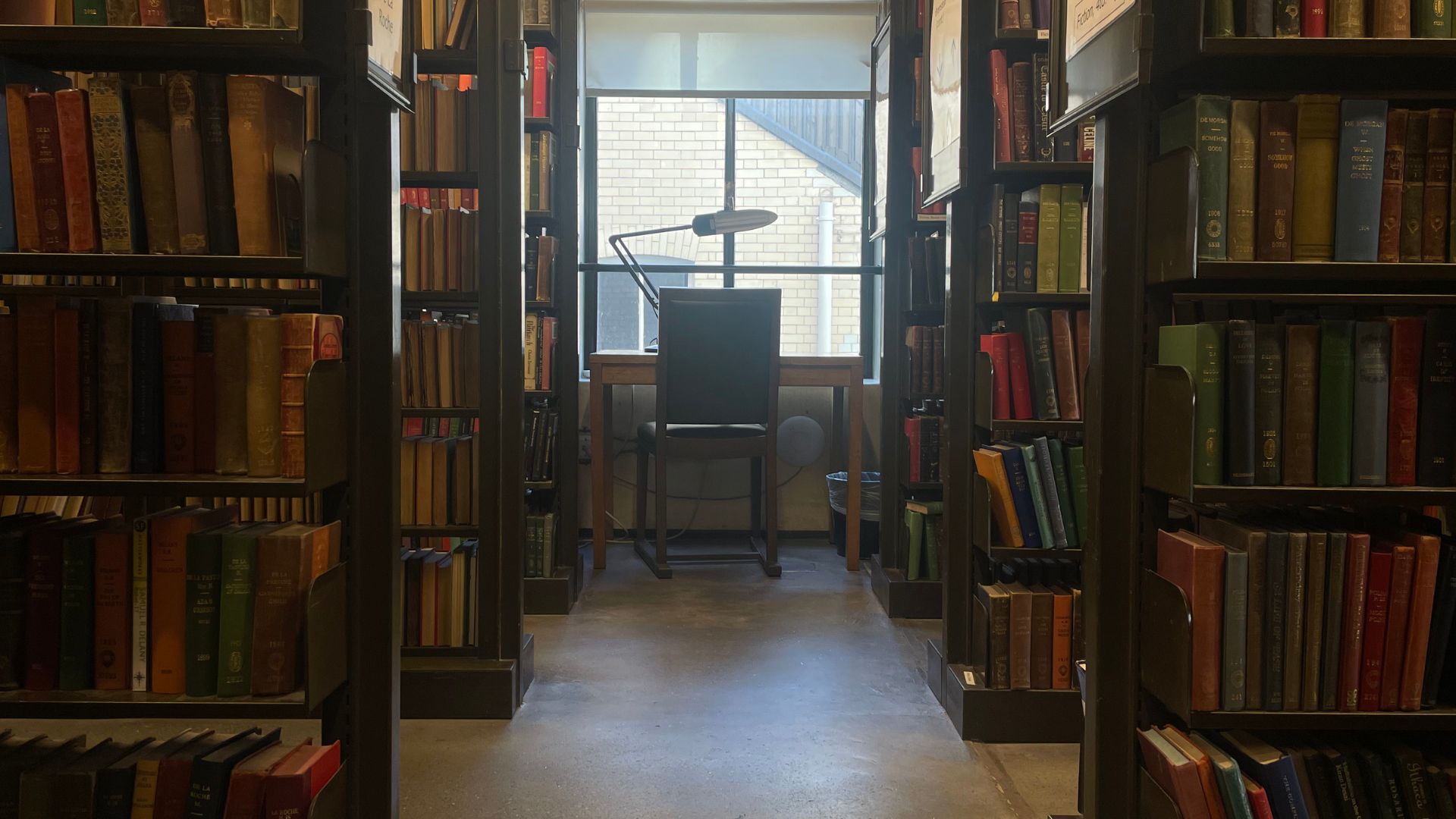

Having twice missed its entrance, I eventually found the Library tucked away in the west corner of the square, between the Cypriot Embassy and the East India Club. Abandoning my coat and umbrella in the Issue Hall, I bounded up the red-carpeted staircase, past the Reading Room and the portraits of the Library’s former presidents, among them Tennyson, Eliot and Leslie Stephen, to the lowest floor of the Literature stacks. It was barely 10 o’clock but the narrow, book-lined passages, with their low ceilings and softly puttering fluorescent lights, gave the illusion of night. Squinting at the jacketless spines around me, I saw that I’d arrived at French fiction – Coulevain to Dumas. Some of the volumes were crisp, sturdy, yet-to-be-taken-out; others carried the marks of time: scuffed edges on brittle, ornate bindings. Wandering further, fishing out books at random, I paused in astonishment at those that were centuries older than the Library itself.

After a few minutes I realized there were two further floors above me, both partially visible through the iron-grille ceilings. With this sudden, dreamlike shift in perspective, the stacks seemed to become extended versions of themselves – towers of books rising up over three storeys. For a moment, it was as though I’d become weightless, suspended, enveloped in literature. Breathing in the scents of dust and old leather, and bewitched by the dim light and the faded russet bindings, I had fallen under the Library’s spell. Much later I discovered that, from the same vantage point, Raymond Mortimer had remarked: ‘I feel inside the brain of mankind.’ That morning I experienced a similar epiphany. Across the chasm of each passageway, it was as if the volumes were communicating silently, with me and one another.

With fifteen miles of books, a history spanning 171 years, and a seemingly endless list of distinguished past and present members, the London Library has, unsurprisingly, developed a folklore of its own. Everywhere you look you encounter the shades of the great. In idle moments I’ve watched Edith Sitwell stare down her nose at the staff behind the Issue Desk. On the carpeted stairway, I’ve passed Eliot and Forster. I’ve held the door to the Gents’ for Dickens. In the Reading Room, I’ve watched a tiptoeing librarian ask the Woolfs to lower their voices. And while researching subjects for the Slightly Foxed catalogue, I’ve even rubbed shoulders with Vita Sackville-West in Topography and Darwin in Science & Miscellaneous.

Since 1841, when Goethe’s Theory of Colours became the first of its books to be borrowed, the Library has been a remarkably generous lender. Even some of its rarest antiquarian volumes can be taken home, and ‘country members’ who live out of town can borrow and return theirs by post. One can only begin to imagine the unlikely corners of the world these books have visited – colonial forts, alpine cabins, farmhouses in the Outback, trading posts on the veld – and that’s before considering the volumes whose globe-trottings preceded their acquisition, such as a collection of medical essays that, in 1790, travelled all the way to Pitcairn on HMS Bounty.

Yet with such literary generosity, of course, there come risks. During the Great War, for example, books were routinely dispatched from St James’s Square to members at the Front. Most were returned in fine condition, but among those lost forever was one struck by a shell, together with its borrower, the poet and critic T. E. Hulme, in a trench in West Flanders. Other casualties include a selection of the Library’s Conrad and Conan Doyle novels that went down with Kitchener on HMS Hampshire and a copy of Mein Kampf flung into the Atlantic by an outraged reader.

The most exceptional provenance, however, must go to G. Fraser Melbourn’s The Planter’s Manual: An English, Dutch, Malay and KehChinese Vocabulary (1894): it sank with SS Halcyon off Folkestone Pier in 1916, was rescued from the depths of the Channel six months later, watermarked but intact, and donated to the London Library. The collection is indeed a wonder, but no more so than the daily stream of readers for whom 14 St James’s Square is a second home. There are some I admire, like the toiling men and women, all curiously alike in their overcoats and sensible shoes, who arrive within a minute of opening time and leave as the doors are being locked for the night. Some I loathe, like the muttering readers, the heavy breathers and the emphatic, two-fingered typists. And some I even recognize – the blonde film star whose presence draws the attention of every youth in the room, and the portly actor, familiar to me from an evening at the Cottesloe, who eyes me through a chink in his armful of books.

Initially, there were members who frustrated me with their seemingly aimless wanderings. But, over time, I grew to appreciate a rare state, exemplified by these blithe spirits, which the Library’s former president Lord Annan described as ‘creative laziness’: that is, ‘reading the books one ought not to be reading, and becoming so absorbed in them and following the trails along which they lead you, so that at the end of the day you still have most of the reading to do that you had before that morning’. This tradition, in itself a tribute to the joys of reading, is alive and well at 14 St James’s Square. And, whether they know it or not, it is the likes of the elderly gentlemen dreaming in the red leather armchairs, the young Rebecca West foraging in Fiction S–Z, and the dandyish fellow scoffing over the periodicals, who are among its custodians.

Now that my year as a member has come to an end, I salute this extraordinary cast of characters and the enchanted labyrinth they inhabit. In any library, as in any book, there are many trails: long may they be followed.

© Richard Conyngham 2012

RICHARD CONYNGHAM is about to cycle from Mexico to Patagonia on a shoestring. In his pannier bags he’ll be carrying a Spanish phrasebook, an abridged Lonely Planet, and a handful of battered Penguins.

From Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly issue 34, Summer 2012 – www.foxedquarterly.com