Claude Joseph Goldsmid Montefiore (1858-1938), great-nephew of Sir Moses Montefiore and grandson of Sir Isaac Lyon Goldsmid, was a member of the Anglo-Jewish elite who broke with Jewish orthodoxy when he founded Liberal Judaism in Britain. By The London Library’s Head of Bibliographic Services Dunia Garcia-Ontiveros, adapted from an article originally written for History Today.

In childhood Claude Montefiore suffered an attack of pneumonia, which left him with a weakened constitution. His delicate health prevented him from attending school and his private tuition was undertaken by both anti-Zionist rabbis and Protestant Christian tutors. This eclectic education planted the seeds of liberal thought that would later move Montefiore to formulate a radically new approach to Judaism. His education continued at Balliol College, Oxford from which he graduated in 1881 with a first in Classics. As one of the top students he enjoyed a close relationship with the master at Balliol, Benjamin Jowett, a believer in religious liberalism who encouraged his pupil to approach the study of Jewish religious texts with a critical eye.

After graduating from Oxford, Montefiore travelled to Berlin in order to train for the rabbinate under the Romanian scholar Solomon Schechter. Montefiore soon changed his mind about his calling and returned to England bringing Schechter with him: becoming an orthodox rabbi was simply incompatible with Montefiore’s revolutionary views on Judaism. He believed that a modern world needed a modern Judaism that didn’t rely so heavily on Talmudic and rabbinic law or on Jewish customs and traditions. His wealth allowed him to devote his life to Biblical scholarship and he offended many Orthodox Jews and Christians with his writings advocating a new religion that combined elements of both Judaism and Christianity: “My originality is my queer mixture, half Jew and half Christian … “. Despite being attacked by members of both religions he was unshakeable in his beliefs.

The second most defining aspect of Montefiore’s thought was the distinction he made between religion and nationality: “In Italy, Holland, France, and, above all, and most supremely in England, a fatherland is not denied to the Jews. (Let the Jews of the United States speak for themselves). Their fatherland is Italy, Holland, France and England respectively”. He saw Zionism as conducive to alienating and segregating Jews from gentiles even further and believed that it only served to make anti-Semitism worse, and even blamed it for the rise of Nazism. On the possibility of Jews settling in Palestine he wrote that it “might involve them in the bitterest feuds with their neighbours … and would find deplorable echoes throughout the Orient”.

A qualified lay preacher, he disseminated his views from the pulpits of both the West London Reform Synagogue and the Liberal Jewish Synagogue and found other platforms such as the Hibbert Lectures delivered at Oxford in 1892 at the invitation of Benjamin Jowett, and the Jewish Quarterly Review, which he founded with Israel Abrahams and co-edited for many years. Still, the man who felt compelled to begin a religious revolution and who was instrumental in the foundation of the League of British Jews, and the Jewish Religious Union for the Advancement of Liberal Judaism was a gentle, prudent and self-effacing individual. While his religious enemies saw him as a man of very dangerous ideas, his political enemies criticised his overly cautious presidency of the Anglo-Jewish Association and most particularly his reluctance to help persecuted Jews on the continent and accused him of being ineffectual. In accordance with his ideas of Jewish nationality, Montefiore felt that the problems Jews faced in other countries had to be resolved locally and often repeated that anti-Semitism was not a problem in England. His main concern was the welfare and the education of English Jews and the list of the philanthropic works he undertook to improve the lives of his compatriots and coreligionists is very long. In fact, Montefiore sometimes complained that these activities and the committee work that a man of his social class was obliged to do, together with his ill health, left him little time to dedicate to his studies.

He was nevertheless able to complete a substantial body of work in the form of several books (The Synoptic Gospels, Some Elements of the Religious Teaching of Jesus According to the Synoptic Gospels, Judaism and St. Paul, Aspects of Judaism, Liberal Judaism, Outlines of Liberal Judaism, Liberal Judaism and Hellenism, Rabbinic Literature and Gospel Teachings, A Rabbinic Anthology, The Old Testament and After, The Bible for Home Reading) and countless pamphlets and articles.

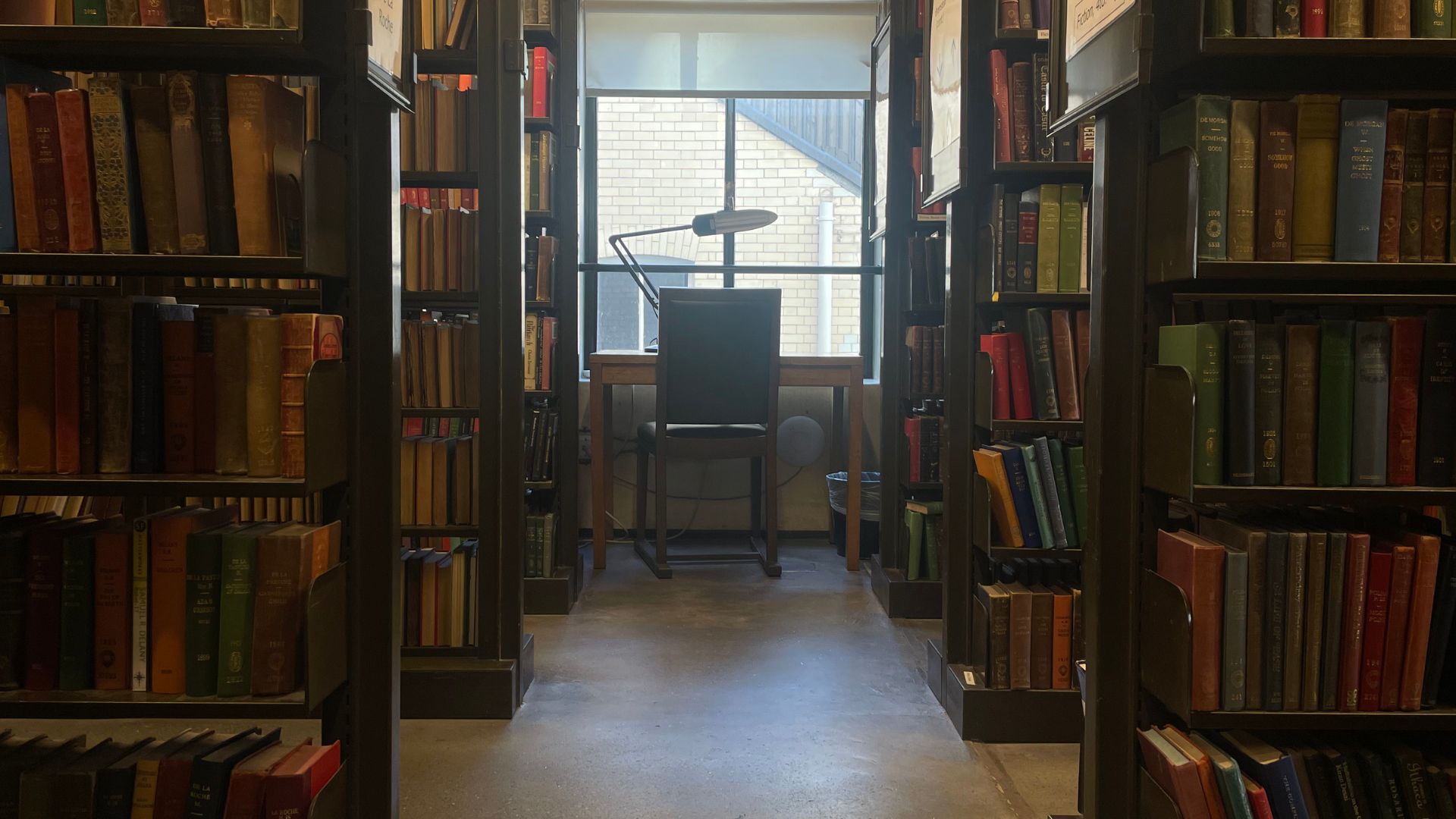

After his death in 1938 the London Library received a bequest of all the pamphlets he collected in the course of his life. The ca. 5,000 titles bound into 664 volumes offer us a comprehensive insight into Montefiore’s mind and all the subjects he was interested in, from theology to social welfare, education and even poetry – his biographers mention that he would often surprise people by spontaneously reciting Shakespeare’s sonnets, a little Tennyson, the preface to Middlemarch or even a fragment of Alice in Wonderland. This explains the presence in volume 454 of a booklet of First World War poems by Janet Begbie, entitled Morning Mist and published by Mills and Boon in 1916 (a few years before the firm decided to concentrate on the publication of romance novels).

By scanning the contents of this and other volumes we can see not only what Montefiore read but more importantly what he chose to keep, perhaps for future reference. A total 161 of the pamphlets in the collection were written by Montefiore himself: Liberal Christianity and Liberal Judaism, What a Jew thinks about Jesus, The dangers of Zionism, Assimilation, good and bad, Is there a middle way?, The originality of Jesus, Has Judaism a future?, On keeping young and growing old, Anti-Semitism in England, Optimism and religion, Is Judaism a tribal religion?, The English Jew and his religion, Jewish emancipation and the English Jew, etc.

Others are written by his mentors and friends: The Chassidim and On the study of the Talmud by S. Schlechter, Poetry and religion and Jewish life under emancipation by Israel Abrahams, The German soul and the Great War and Progress in religion by Baron Friedrich von Hügel. Some are even written by his enemies: The racial conception of the world and The Nazi party, the state and religion by Adolf Hitler, Chosen peoples: the Hebraic ideal versus the Teutonic and A land of refuge by Israel Zangwill.

The pamphlets are bound in rough chronological order and this arrangement also allows us to trace the developments in scholarship and world events taking place around Montefiore. These range from Biblical criticism and Reform Judaism to the work of Jewish charities and social responsibility.

The earliest pamphlet Kritische Untersuchungen über den menschlichen Geist, oder, Das höhere Erkenntniss- und Willensvermögen (Critical examinations of the human spirit, or, The higher knowledge and volition) by Salomon Maimon dates from 1797 and the latest Public development and slump control by The Next Five Years Group is from 1938, proof that Montefiore was actively interested in the welfare of others almost to the very end of his life.

This scholar, philanthropist and reformer, described by some as a saint and by others as class-conscious snob who abhorred socialism and was suspicious of democracy, died “disappointed and embittered” at the relative failure of Liberal Judaism, which he blamed on the rise of Zionism.

Discover The National Portrait Gallery’s portrait of Montefiore by Sir William Rothenstein circa 1935 in its Later Victorian Portraits (online) catalogue – Montefiore portrait