June marks the month in which the Sami Act of 1987 granted cultural autonomy and democratic representation for the indigenous Sami people of Norway. Our latest blog by Head of Bibliographic Services Dunia Garcia-Ontiveros explores the 18t century linguist and ethnologist Knud Leem who devoted his working life to the Sami people and their language. Adapted from an article originally written for History Today.

The missionary and linguist Knud Leem was born in 1697 in Haram, eastern Norway. He read theology at the University of Copenhagen between 1713 and 1715 and after completing his examinations he began to study the language of the indigenous people of Lapland. The Sami people, formerly known as Finns and Lapps, inhabit a region of northern Scandinavia that includes territories in Norway, Sweden, Finland and Russia. Norway has always had the greatest Sami population, concentrated in the northern region of Finnmark (‘Sami country’).

The eighteen year old Leem was very interested in the Sami people and hoped to work as missionary in Finnmark but realising he was too young he began his professional life working as a tutor and as an assistant to senior clergymen in the town of Møre in Western Norway. He first applied to the Missionary Board for a post in Finnmark in 1723 but he had to wait another two years before a position became vacant. Finally, in 1725 Thomas von Westen, the ‘apostle to the Lapps’ who was in charge of the mission to the Sami from 1716 to his death in 1727, sent Leem to Porsanger, in Finnmark.

Leem spent the next ten years among the Sami people of Finnmark, leaving Porsanger to become a pastor in Alta-Talvik in 1728, where he expanded his knowledge of their language, their beliefs and their way of life. When in 1735 he left Finnmark to take up the post of pastor in Avaldsnes, southern Norway, his quest to educate Norwegian missionaries in Sami culture and to improve the spiritual and material life of the Sami had just begun. In 1748 his En Lappisk Grammatica Efter den Dialect, fom Bruges af Field-Lapperne udi Porsanger-Fiordenwas published in Copenhagen. It was a grammar of the Karasjok dialect, the language spoken by the mountain Sami in the Porsanger Fjord. The work was completely original, based on Leem’s own observations and not relying on earlier grammars published in Sweden. The book was aimed at fellow missionaries and in writing it Leem fulfilled one of the classic roles of the Christian missionary: to break down language barriers in order to facilitate religious conversion. Although considered by some to be inferior to the earlier Swedish Sami grammars it remains the first surviving scientific work on the Sami language published in Norway: earlier works produced in the Trondheim seminary under the auspices of Thomas von Westen were destroyed in a fire in Copenhagen in 1795.

Having completed his grammar, Leem lived in Copenhagen for a year and began work on his magnum opus, the Lexicon Lapponicum Bipartitum. The first part of this great Sami encyclopaedia was published in Trondheim in 1768 while the second was published posthumously in Copenhagen in 1781.

Flying the flag for the Norwegian Sami people was not an easy task. The Kalmar Union of 1397 had brought Norway, Denmark and Sweden together under a single head of state. In practice this meant that while foreign policy was dictated by the monarch each country retained a great degree of legal and administrative autonomy, which inevitably led to tension and conflict. In 1523 Sweden left the union and in 1536 the Kalmar Union was formally ended when Denmark took over control of Norway. The Danish domination continued until 1814 when after the defeat at the Battle of Copenhagen Denmark was forced to sign the Treaty of Kiel and effectively hand over control of Norway to the victorious Sweden. As professor Gutorm Gjessing of the Universitetes Etnografiske Museum of Oslo wrote in 1947 “ … the historical development of the country has provided too good a soil for cultural isolationism and national self-communion.” In other words, a nation struggling with the daily reality of being ruled by a foreign power will have little sympathy for or interest in a “primitive” ethnic minority that inhabits a remote corner of the country.

In the 18th century the Danish-Norwegian government was immersed in boundary controversies with the Swedish government and Sweden began to show an interest in the Sami people who lived in disputed lands. The Danish-Norwegian mission to Finnmark was therefore both a religious and political enterprise with the dual goal of making the Sami Christian and Danish. Whichever country could claim the Sami would have a much stronger claim to the land they occupied. However, different bishops had very different views on how best to achieve this aim. Peder Krog, bishop of Nidaros from 1689 to 1731 and his successor, Eiler Hagerup, both believed that the answer to the problem was to teach them Danish so their conversion to Christianity could be carried out in the national language, but others were completed opposed to this approach. Thomas von Westen defied Krog when in 1717 he opened a seminary in Trondheim where missionaries destined for Finnmark were taught the language of the Sami by the schoolmaster and translator Isaac Olsen, who was also Knud Leem’s teacher. Von Westen managed to keep the seminary going in the face of Episcopal disapproval but the school was closed the moment its founder died. Hagerup’s successor, Ludvig Harboe, who became Bishop of Nidaros in 1743, understood the need for priests and missionaries who could speak, read and write in Sami and so did Frederik Nannestad, who succeeded him 1748. In 1750, Nannestad approved a request from the Missionary Board to set up a new seminary, led by Knud Leem, where Sami could be taught. On Leem’s advice the location of the proposed new school changed from Alta to Trondheim and in March 1751 the Seminarium Lapponicum Fredericianum opened its doors. The need for Sami-speaking Norwegian and Danish missionaries became even greater when the border dispute with Sweden was finally settled that same year with the signing of the Strömstrad Treaty. The treaty gave the Sami people the right to roam freely across the agreed new border, making it easier for the Norwegian Sami to go to Sweden in search of Sami-speaking priests.

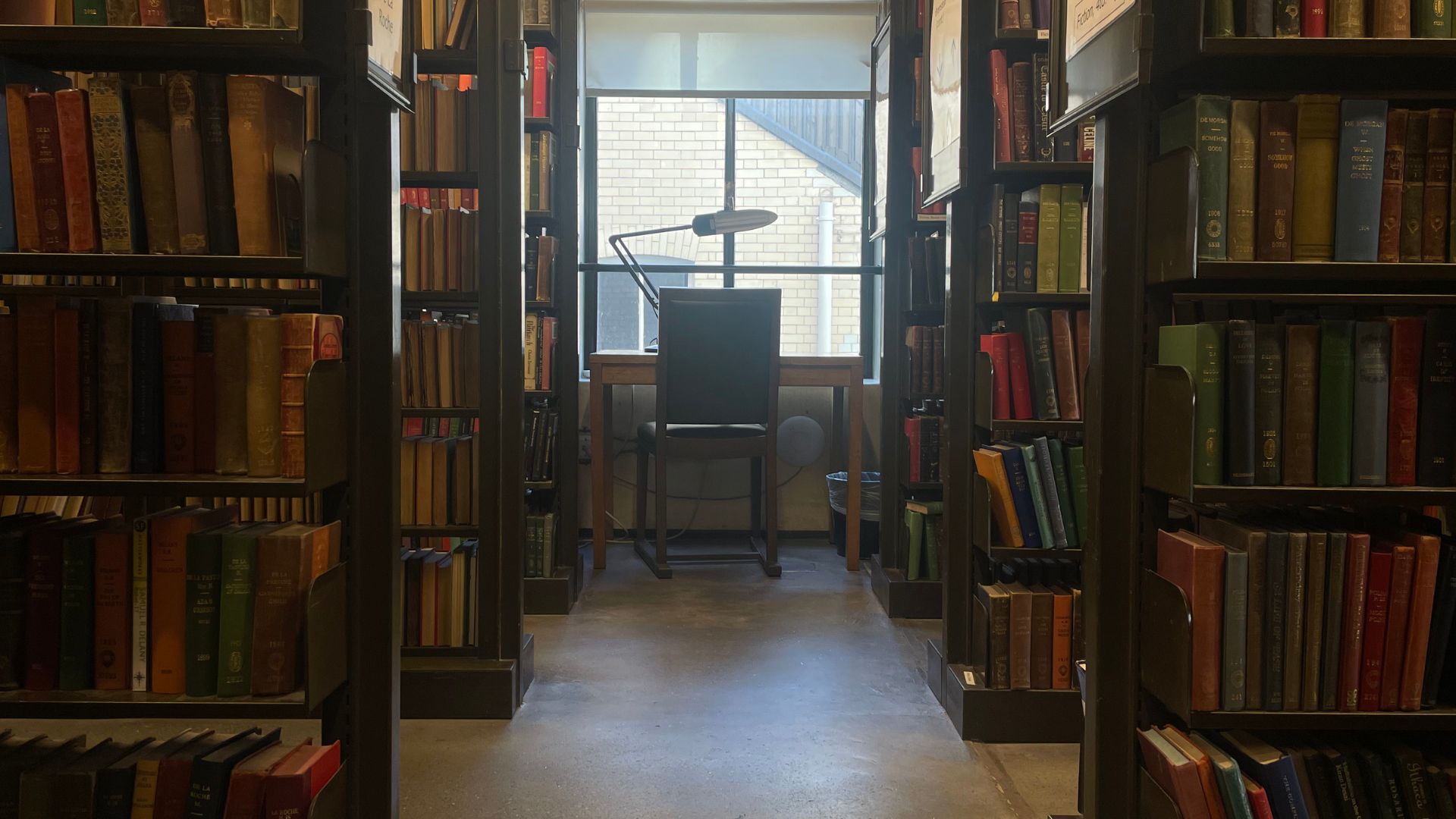

Leem devoted the rest of his life to running the seminary and its associated Latin grammar school. Much of his time was invested in trying to resolve the tensions caused by the fact that he admitted Sami students to be taught alongside Norwegian and Danish students. Gerhard Schøning, the rector of Trondheim Cathedral believed the Sami to be an inferior race and made a very public protest when he removed his cousin from the school. Nevertheless, with the support of Bishop Nannestad and his successor, the theologian and botanist Johan Ernst Gunnerus, Leem was able to keep the seminary and the school going and even found the time to continue to publish books on the Sami language and culture. In 1756 he published a Danish-Sami dictionary and in 1767 the work he is most remembered for, Beskrivelse over Finmarkens Lapper. This comprehensive ethnological study of the Sami of Finnmark includes some notes on ornithology written by Gunnerus. The large volume, held by the London Library, contains over 600 pages of parallel Danish and Latin text and 101 leaves of beautiful illustrations depicting every aspect of the life of the Sami, their dwellings, costume, reindeer herding and fishing techniques. Because of this book, the man who had set out to bring a remote group of people closer to Christ is now remembered as one of Norway’s first ethnologists of the Finnmark Sami.

History repeated itself when Leem’s seminary closed its doors soon after his death in 1774 and for the next 200 years Norwegian attitudes towards the Sami worsened. Writing in 1953 Professor Gjessing cited a number of factors that contributed to the anti-Sami prejudice from the mid nineteenth century onwards. These included the rise of evolutionism used to support the notion of inferior races, a growing nationalism and “Norwegianization” of school education as a reaction to Swedish domination, the industrial revolution which created the notion that culture was synonymous with industry, and legislation that prevented non-Norwegian speakers from owning land in Finnmark. The situation did not improve when Norway finally obtained its independence in 1905: the Sami faced a more immediate problem when the profitable trade with the Russian Pomors began to decline at the beginning of the 20th century and then disappeared completely after the Russian revolution.

Norwegian attitudes changed after the Sami joined the Resistance during the German occupation of Norway, which began in 1940. In 1959 a change in the law allowed Sami children to be taught in their native tongue and the Sami are now recognised as the indigenous people of Norway. In 1989 the Sami Parliament was opened and in 2005 the Finnmark Act transferred property rights to land and water to the Sami people.