We explore Lady Colin Campbell's 1903 book “A Woman’s Walks”.

As a woman who had to reinvent herself and become self-sufficient after being at the centre of the most notorious divorce scandal of the 1880s, Lady Colin Campbell (1857-1911), was the embodiment of the independent, intrepid and outspoken author.

Following the separation from her husband she was largely exiled from society but became a prolific author, art and literary critic, playwright, novelist, essayist, translator, newspaper editor and journalist, contributing to the Saturday Review and the Pall Mall Gazette. She was also an artist, a talented singer and an accomplished sportswoman who could speak and write authoritatively on a broad range of subjects and enjoyed the friendship and patronage of George Bernard Shaw (who described her writing as “impudently amusing”). Her formidable spirit was actually set free by her fall from grace and nowhere is this seen more clearly than in A Woman’s Walks: Studies in Colour Abroad and at Home (1903).

Originally published in issues of The World, from 1889 onwards under the pseudonym Vera Tsaritsyn, it is a collection of short pieces on her travels in Italy, France, Switzerland, Austro-Hungary, London, and the English countryside. Vera, as she was known to her friends, revisits some of the places where she spent her childhood, such as Venice, but also ventures into locations new to her. The pieces, from which we have reprinted only a selection, vary widely in tone and subject matter. There are beautiful mountain landscapes, sun-bathed lagoons, candle-lit churches and quiet gardens but there are also busy railway signal-boxes, noisy and dangerous workshops, the smells of the fish market and the squalor of dirty little back gardens in south London. The author is often accompanied by friends (to whom she dedicates the book) and who are sketchily described and sometimes affectionately mocked:

“The Expert, wishing to note whether his gear-chain is all right, walks a little distance, and can hardly keep his feet at all on the slippery surface. With relief he finds himself once more in the saddle, and, catching us up, is explaining the matter to me, when, as the words “These tyres really seem to hold better on this road than shoes” leave his lips, the demon that invariably lurks in a bike seizes the opportunity. Before he can enunciate the word “shoes” the wheels slip as if mowed down by a scythe, and I have just time to spurt violently ahead to avoid being bowled over by h

is downfall. I grieve to say that the Gemini and I are so shaking with laughter at the psychological moment chosen for the mishap that we can only just make friendly inquiry over our shoulders.” (p. 125-126)

The characters she encounters are not usually treated with quite as much kindness:

“ … these fat female Teutons, with red, perspiring faces, surrounded by straggling wisps of sandy hair, clothed in men’s shirts and boots and much-abbreviated skirts hitched up with straps round their middles (one could not give the name of waist to such equatorial lines !) and their Falstaffian companions, entirely spoil the beauty of the scene for me.” (p. 60-61)

But it is this uncensored voice that makes the book come alive. Lady Colin Campbell shares her exhilaration with us:

“Dogged determination not to be beaten, however, makes victory but a question of time, and, once conquered, the bicycle becomes a friend, an ally to be depended

upon at all times and seasons, an endless delight. To it one owes not only the feeling of absolute independence, of self-sufficiency in the truest and best sense of that much ill-used term, but the knowledge of the sensation of flying.” (p. 82)

Her dread:

“I have visited many graveyards, but always with horror and reluctance, as my mind persistently dwelt upon and realised the unspeakable abominations of physical corruption. Besides, the idea of being hidden in a hole in the ground, away from the light and heat of the sun, has always oppressed me like an evil dream; but as I leave the crematorium of Milan I am conscious of nothing but a radiant vision – a chariot of flame to close my earthly record … “ (p. 56)

And her joy at venturing outside again after a long illness:

“ … seeing a door open in the wall on the left, we pass through it, and find ourselves in a delightful garden, a great stretching space of velvety green turf, with glorious trees. After my imprisonment, such a place is like a glimpse of paradise. “ (p. 243)

But what really shines through is her love of freedom and adventure:

“I ought, by all the rules that should govern the mind of a sensitive, proper-minded female, to be overcome with dismay at finding myself friendless, soap-less, comb-less, curling-tong-less, alone and unprotected in a strange city “as the clocks are chiming the hour” of midnight! But I am not; or rather, when I realise the entire novelty of the situation, I am so overcome with a sense of exhilaration at being for once in my life absolutely free, with no more responsibility than a bird on the wing, that I very nearly dance a rigadoon of delight on the dusty metals of the line before an advancing engine! … I hum to myself as I stand looking up at the sky, filled to overflowing with the joy of liberty, and swaying to the lilt of the seguidilla [a Spanish dance]. Nobody knows where I am; nobody (here in Milan) cares what I do” (p. 50)

“No! A companion is not always either a thing of beauty or a joy for ever; he or she is often a stopper in a vial of perfume, a discordant note in the otherwise perfect harmony, an ever-present weight. Like trout fishing, bicycling has joys that are unknown to those who seek them not in solitude”(p. 84)

And her wicked sense of humour:

“I am awakened by the connubial warblings of an unmistakably American couple in the next room. Dear me! what strange forms of expression Yankee matrimony takes upon itself in privacy, or at least what it is pleased to suppose is privacy!” (p. 51-52)

“We are not lucky, or else we possess some unknown and undesired attraction for fat Germans; for four of the fattest specimens tumble into our compartment … Jokes born of wine nearly produce apoplexy in my opposite neighbour, an individual whose face might be taken for that of” The Man in the Moon”; when, mercifully, one of the four starts humming a tune, another produces a well-thumbed book of Yolks-Lieder out of his pocket, and the four launch into part-songs with undeniably sweet voices, which is a distinct improvement on their guttural conversation and loud guffaws … They continue to warble softly and pleasantly, like four fat red bullfinches; and the blue gooseberry eyes of my opposite neighbour are full of tears as he ecstatically sings what will happen “Wenn ich komm, wenn ich komm, wenn ich wieder urn komm” (his vision will probably materialise into chastisement with a broomstick by the wife of his bosom if he returns to her in his present condition!) as we draw up at Caux, and leave the bullfinches to warble alone.” (p. 61)

It is terribly sad to think that only three years after the book was published trout-fishing, fencing, cycling, globe-trotting Vera spent the following five years withdrawing from the world until her premature death at the age of 53. Having read about her fear of being buried one can only feel relief at finding out she was cremated.

Jane Haslam looks at the story behind one of the most remarkable items in The London Library’s collection – an original, and extremely rare, copy of one of the three editions of Martin Luther’s Ninety-Five Theses known to have been printed in 1517.

Just over five hundred years ago, during Vespers on All Hallows’ Eve in 1517, a notice appeared, nailed to the door of the Castle Church in Wittenberg (an emerging Saxon town in North-East Germany), inviting discussion over the sale of Papal indulgences in the neighbouring provinces of Brandenburg and Saxony-Anhalt. It was usual practice to advertise topics for academic debate on the church doors of University towns – a notice board for a captive audience. This particular disputation was authored by Fr. Martin Luther, an Augustinian friar, doctor of theology and University lecturer. The text ran to a total of ninety-five items for discussion and, as every school child knows, Luther’s action is considered to pin-point the exact moment when the Reformation began. Within months the German Church was in ferment and Christendom torn asunder. The repercussions have reverberated throughout half a millennium.

The process of affixing notices to church doors was so familiar, so ordinary, that no-one thought to make record of the moment. We are left in the dark as to whether Martin Luther’s Ninety-Five Theses were printed or hand written, whether they were nailed solely to the Castle Church door or onto every other church door in Wittenberg and, most significantly, whether they were nailed or posted anywhere at all. Academics have been, and remain, divided as to the veracity of the story.

The selling of Papal indulgences was an established practice – guilty sinners would part with their money and receive in return letters of safe conduct through Purgatory for themselves and their deceased relatives. The advent of the printing press during the 1440’s had enabled the mass production of indulgences. Producing more meant selling more; boosting the income of the Church. Sales of indulgences had been banned by the Elector Friedrich in Saxony but many Wittenbergers crossed the border into Brandenburg and Saxony-Anhalt attracted by Johannes Tetzel, a well-known indulgence preacher.

The question remains how a pedestrian call for debate became the spark from which the Reformation took light. Luther maintained his innocent intentions, but there can be no doubt that once he realised what was happening, and saw how eagerly and quickly his Theses were shared and re-printed, he undertook to mobilise one of the greatest populist movements in history.

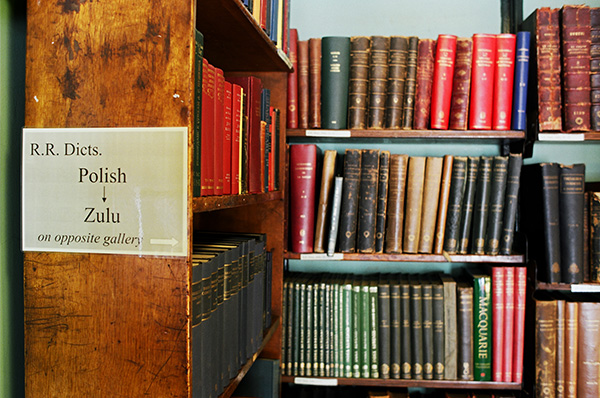

Over the centuries, many words have been written about the Reformation, millions of which have been published over the past year or so alone. A quick scan of the London Library Catalogue turns up dozens of monographs and articles, and in this quincentenary year prominent religious and academic institutions are holding conferences and symposia and mounting real and virtual exhibitions.

The London Library is commemorating too because we hold one of the very few remaining copies of the Ninety-Five Theses that were printed in 1517.

Three editions are known to have been printed at the time and it is thought that each were printed within a fortnight of the nailing of the disputations to the church door. There are two broadsheet or placard editions – attributed to printers Joseph Thanner of Leipzig and Hieronymus Höltzel of Nürnberg – and one quarto or pamphlet edition attributed to Adam Petri of Basel. The Library holds an original from the Petri print run.

(Left: The Thanner broadsheet – printed by Joseph Thanner of Leipzig – is set with haste and contains numerous setting errors. Right: The Höltzel edition: attributed to printer Hieronymus Höltzel of Nürnberg and the second of the two broadsheet or placard editions)

The three editions show us how swiftly the word was spreading in late 1517. The Thanner broadsheet is set with haste, untidy and full of mistakes. The compositor, clearly under pressure, numbers each thesis in sequence using Arabic numerals but becomes muddled as item 24 becomes 42; 27 becomes 17; and 46 hovers in the middle of item 45, 75 in the middle of 74 leaving a nominal tally of 87. The Höltzel impression is neater and cleaner; an experienced compositor uses Arabic numbers in three sets of twenty-five and one of twenty, a pilcrow marks the beginning of each.The Petri pamphlet uses lower case Roman numerals in sets of twenty-five and twenty, each piece of text is indented. Not as cleanly set as the Höltzel impress, the Petri has a standard print-shop woodcut capital ‘D’ as decoration but the composition is a little loose. During the printing of the Library copy, it appears an enthusiastic or possibly harassed apprentice over inked the type face prior to the paper being laid upon it and the printed sheet was not pulled cleanly from the press. Once the paper had dried our copy was folded twice to make the quarto pamphlet, sent from Petri’s print shop, and distributed from Basel.

Unfortunately, it is impossible to ascertain where our Petri edition went from there: the provenance of the London Library copy is sketchy and open to conjecture. What we know for certain is that The London Library acquired it in 1921. It was delivered to St. James’ Square from the Methodist Central Hall in Westminster which was acting as a temporary repository of The Allan Library. Thomas Allan was a 19th century bibliophile and his passion drove him to scour Northern Europe for any and every book of a religious theme. Charles Theodore Hagberg Wright, Librarian, was eager to acquire this substantial collection in order to supplement The London Library’s German Collections in which he had a specific interest. Thanks to a lack of commitment by the Methodist Conference, and canny manoeuvring by The London Library, a huge resource of 21,500 volumes packed with historically significant gems was had for a song and the Ninety-Five Theses came to The London Library as part of that collection. Today, Allan’s acquisitions not only supplement and enhance the Library’s enviable German Collection but they also form the substantial core of the Library’s Special Collections.

One can only guess where this copy of the Ninety-Five Theses was during the three hundred and fifty years prior to Thomas Allan acquiring it in the early 1860s. Unfortunately, his acquisition records and invoices have not survived, so it is impossible to pin down where any of the collection originated or how much it cost. Thomas Allan stored his collection in packing cases in Baker Street until he gifted it to the Methodist Conference in 1886 where the majority remained packed away, firstly on City Road and then at Methodist Central Hall in Westminster. On transferring to St James’s Square the Ninety-Five Theses was catalogued on 28th October 1921, bound between plain boards and shelved in the recently constructed new glass floored stacks. This seemingly insignificant four-page pamphlet then survived nearly eighty years on the open shelves. When the Anstruther Wing opened in 1999 to house the Special Collections, Allan’s Reformation books were transferred there and it is where our pamphlet now resides in a dust-free, temperature-controlled environment.

It doesn’t matter whether Martin Luther nailed his Ninety-Five Theses to the Castle Church door in Wittenberg or not, the story survives, as does one of only a handful of copies of the only contemporary quarto printing. Half a millennium after it was pulled from the press, now newly bound and about to be digitised, the London Library copy of the Petri edition of Luther’s Ninety-Five Theses reaches its quincentenary both treasured and preserved.

The London Library’s copy of the Petri pamphlet edition. The type face was over-inked prior to the paper being laid upon it and the printed sheet was not pulled cleanly from the press.

Margaret Gabrielle Vere Long's membership form was recently discovered while completing a collection care condition survey of membership form bindings. Interestingly the form is different from most others because her writing pseudonym is included beneath her signature.

"Marjorie Bowen" is one of many pseudonyms Long used as a writer. She was a prolific British author who wrote historical romances, supernatural horror stories, popular history and biography. Long wrote over 48 books under male pseudonyms including Joseph Shearing, George Preedy and Robert Paye. As "Marjorie Bowen", Long's female pseudonym, she wrote over 150 books, achieving international acclaim and two novels adapted for the big screen.

Long wrote her first published novel, The Viper of Milan, at the age of 16. A number of publishers rejected it claiming that someone so young wasn't capable of writing such a story. Her Shearing novels were especially popular in the United States, with many of them becoming both critical and commercial successes. The true identity of Shearing wasn't known until the late 1940s.

In addition to fiction, biography and crime Long also wrote gothic horror whose work was well respected. During an interview for the Autumn 1953 Paris Review, Graham Greene stated “I chose Marjorie Bowen [as a major influence] because...I don't think that the books that one reads as an adult influence one as a writer...But books such as Marjorie Bowen's, read at a young age, do influence one considerably."

Long's early life was not an easy or happy one. Her father died of alcoholism and her mother was an aspiring writer. The family was poor and were known to move around to avoid paying off accumulated debts. When Long received £60 for her first work, she surrendered it immediately to her mother who was jealous of her success and became increasingly embittered. All of Long's money was banked in her mother's name, and was spent as fast as she earned it. Long seemed always panicked into writing for money, and never stopped being the family breadwinner. The discord affected her so badly that in 1939 she wrote a brutally honest account of her life in The Debate Continues.

The Library holds a number of Long’s volumes, under all her pseudonyms, on the open shelves, along with her biography written under her given name, Margaret Campbell. If you are visiting the Library, there is a small display of her work and biography in the Reading Room.

Read more: Amongst the Members: Margaret Gabrielle Vere Long

Mary Shelley and the Birth of Frankenstein

With Miranda Seymour

Mary Shelley’s great novel “Frankenstein: or the Modern Prometheus” was first published in January 1818.

Behind the tale of this remarkable novel is the tale of its extraordinary creator - Mary Shelley – who was just 19 when, on holiday with Percy Bysshe Shelley and Lord Byron in 1816, she first conceived the idea for the story that shook the world.

At this event Miranda Seymour - author of the definitive Mary Shelley biography. Miranda will be exploring the writing of the novel and the intricacies of Shelley’s life in a fascinating talk, woven around selected readings from Frankenstein and shining a light on the personality behind one of literature’s great classics.