Angelographia sive Pneumata Leityrgika Pneumatologia, or, A Discourse of Angels, their Nature and Office or Ministry, published in London in 1701, was according to Rodney M. Baine “the last thorough treatise [on angels] published in England in the tradition of the previous century”[1]. Baines is referring to the growing scepticism, where angels are concerned, found in 17th and early 18th century England and referred to by the book’s editor, George Hamond, who blames it partly on the ‘irreligiousness of materialists.’

The obscure minister Richard Saunders, author of Angelographia, was apparently the last author willing to proclaim his belief in the existence of angels and show “what excellent Creatures they are …”, albeit anonymously. The book, published nine years after Saunders’ death, appears at first glance to have been written by someone who had intimate, first-hand knowledge of God’s messengers. In fact, Saunders doesn’t claim to have had any personal encounters and cites the Scriptures as his only source. Furthermore, he criticises “the Presumption of the Schoolmen and Papists … who undertake to give the World so particular account of this [the order of angels], as if they had lived among them, and seen their Manners and Government.”

Saunders begins his book by discussing the various appellations given to angels, such as Messengers, Elohim, Morning Stars, Seraphim, Cherubim, Watchers, Thrones, Dominions, Principalities, Powers, Intelligences, Abstract and Separate Forms, Dæmons, and Genii and explains how the names “express somewhat of their nature and properties”. He also writes that there are three kinds of spirit: intellectual, sensitive and vegetative and he states that God and His creations, that is, angels and ‘humane souls’ all belong to the first category. He then goes on to ponder more practical matters, such as whether angels are incorporeal or appear in physical form, the date of their creation, and the extent of their powers.

Saunders claims that they cannot work miracles themselves even though they are enormously agile and as swift as the winds, which is why, the author explains, they are often represented with wings. However, the author does list the sorts of missions angels are sent to perform, from making men prosperous, to warning them of danger and even discovering and restraining enemies, providing comfort and easing the pains of death. Wanting to avoid popish presumption Saunders does not offer any information on angelic hierarchy but when it comes to estimating the number of angels in existence he writes that ‘there are very great Multitudes of them. In all likelihood, as there is a World of Men, so there is a World of Spirits, and they inhabit the Regions above us’. As to the name of their ‘Habitation’, the author tells us that it is the ‘Empereal Heaven or the Heaven of the Blessed’.

Saunders is in awe of these instruments of God but to him their most important quality is their ‘great love to Mankind’ and he urges men to return that love and not offend these benevolent spirits. His attitude is clearly at odds with that of other Protestant theologians busy attacking the Catholic scholars who wrote on angelology for spending time on ‘nice and idle’ questions. Thomas Aquinas was particularly ridiculed with the question “How many angels can sit on the head of a pin?” after he wondered whether several angels could be in the same place. Surprisingly, given the unpopularity of the subject at the time the book appears to have been something of a success. Quite a few copies have survived and The London Library volume has had at least three famous former owners, two of which who have left their bookplates pasted on the volume’s endpapers.

The first was Henry Francis Lyte (1793-1847), hymn writer and author of ‘Praise, my soul, the king of heaven’ and ‘Abide with me’. Lyte suffered from asthma and his delicate health prevented him from having a stable and profitable career in the Church. He spent much of his life moving from one curacy to another and in his later life he went abroad for long periods of time for the sake of his health. He died at the age of fifty while he was staying in Nice and the following year his extensive library was sold in London.

The man who bought Lyte’s copy of Angelographia was none other than Richard Monckton-Milnes, first Baron Houghton (1809-1885), author and politician and President of the London Library after Thomas Carlyle’s death in 1881. ‘Dickie Milnes’ collected books on many subjects, including theological curiosities and he must have been quite pleased to find Saunders’ treatise on sale among Lyte’s books complete with Lyte’s bookplate depicting a coat of arms with four swans (representing music and poetry).

When Monckton-Milnes died the book passed into the possession of his son, Robert Offley Ashburton Crewe-Milnes, marquess of Crewe (1858-1945). A poor orator, described as being ‘slow of thought and slower of speech’, Crewe allegedly caused one of his listeners to lose her sanity. He preferred reading to public speaking and he certainly had plenty of to choose from among the many books he inherited from his father, even after he disposed of his progenitor’s erotica collection. It is Crewe’s elaborate armorial bookplate that we find on the endpaper facing Lyte’s much plainer ‘ex libris’. Crewe was a reliable public administrator but had an intense dislike of financial matters. This, coupled with extravagant behaviour saw his inherited fortune greatly diminished by the time he died, which may explain why the book did not remain in his family’s possession.

A pencil inscription above Crewe’s bookplate shows us that the book was owned by Maggs at some point and a stamp on the verso of the title page represents the final chapter in the book’s history when it is accessioned by the London Library on 12 March 2002.

To the sceptics who may wonder why apparitions are so rare in modern times Saunders explains that these are no longer as necessary as they once were when the Church was in its infancy and the Scripture was not yet written so that people needed constant ‘sensible entercourse [sic]’ with angels in order to believe in God, whereas now we only need ‘insensible communion’ with them, often in the form of dreams. Saunders finishes his book by exhorting readers to imitate the example given by angels to live a better life ‘in humility, patience and long suffering, in charity, in integrity, universality, punctualness of obedience, in zeal and diligence and in constancy and unwearidness’. This last quality would seem the hardest to attain, particularly for those working long hours and travelling great distances every day to earn a living. Still, as Saunders says: “If we be weary in our bodies, yet we should not in our Spirits. Some services will unavoidably tire the body, but such weariness is none of our Sin, if our Spirits be not tired, but we continue patient in well-doing”

[1] Baine, Rodney M. Defoe and the Angels. Texas Studies in Literature and Language, Vol. 9., No. 3 (Autumn 1967), pp. 345-369

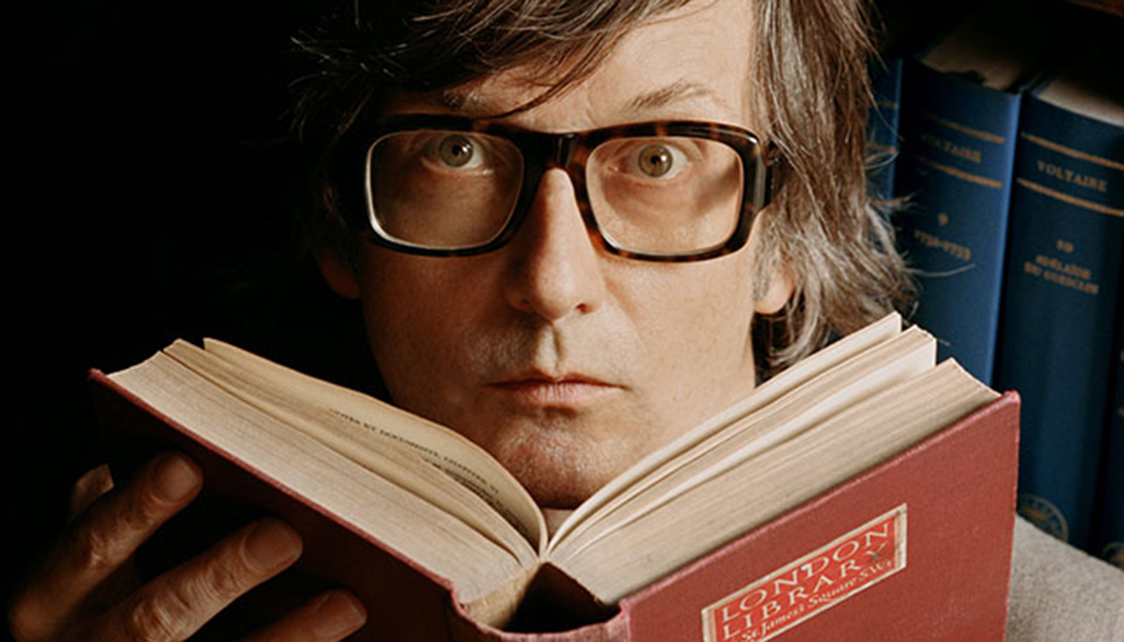

The London Library is more than fortunate to boast some of the most helpful and courteous Issues Desk staff that one could hope for. For the first half of the twentieth century, however, members would have experienced a rather more ambiguous welcome as they entered the Library under the terrifying gaze of the legendary Frederick James Cox who manned the Issue Desk for several decades until his retirement in 1951.

Cox joined the Library as a messenger boy in 1882, at a time when a number of members, including the Duchess of Cleveland (Prime Minister Lord Rosebery’s mother), were still arriving on horseback. He continued working until the age of 86 – a career spanning nearly 70 years, during which he came into contact with an extraordinary range of public figures, from Gladstone to Somerset Maugham; Randolph Churchill to Evelyn Waugh; Thomas Huxley to Rose Macaulay.

Dressed in wing collar and studs and fronting the Issue Desk like an imperious bank manager, Cox became a London landmark, sketched by Punch and frequently remarked upon by members amazed by his encyclopaedic knowledge, intimidated by his overbearing manner, and all too frequently patronised by his sharp sense of humour.

JW Lambert, Editor of the New English Dramatists series, recalled how “the presiding genius of the Issue Desk always made me shake in my shoes, riven by the conviction that I should not be taking out whatever I was taking out, or that I was transgressing some unwritten law or another”.

Cox rounded on those he disapproved of. He refused to acknowledge JB Priestley’s success, asking Priestley to repeat his surname more loudly in front of everyone at the Issue Desk so that Cox could fill in the borrowing form properly. When an embarrassed Priestley obliged, Cox barked: “Initial?”

Lady Galway – daughter of Sir Rowland Blennerhassett, one of the leaders of the English liberal Catholic movement – found herself searching for an interpretation of a passage in the Book of Revelation. Cox instantly identified the appropriate authority: “Sir Rowland would have known” he said, frowning at her.

Edith Sitwell was snubbed altogether. JW Lambert recalled, “There appeared through the entrance doors a startling vision: a tall thin woman with an ivory profile and imperious carriage, followed at a respectable distance by a chauffeur with his cap tucked under his arm and carrying a pile of books. She addressed him (Mr Cox) with all the confidence of birth and fame. He broke off what he was saying to me, paused and without turning his head uttered … ‘One moment, Miss Sitwell, if you please’, before carrying on, for several minutes whatever it was that he was telling me”.

Concerned at the treatment of books by some members, Cox remonstrated with Frank Pakenham (later Lord Longford) who was returning several books, one of which had a page turned down. Cox bellowed, “Right, you just wait there!” Moments later he returned, and slammed a pile of books onto the desk, all of them with pages turned down. He roared, “I’ve been lookin’ for the culprit for some time!”

Cox was no less able to hide his disdain for Virginia Woolf when a friend of hers asked for a copy of The Voyage Out. “By Virginia Woolf?” he asked. “Let me see; she was a Miss Stephen, daughter of Sir Leslie” (Leslie Stephen was a former Library President). “Her sister is Mrs Clive Bell I think. Ah, strange to see what’s become of those two girls. Brought up in such a nice home too. But then, they were never baptised”.

Yet for all his idiosyncracies and inverted snobbery, this man – who spent nearly three quarters of a century serving, sometimes insulting, and often intimidating some of the greatest names in literature – was revered for his vast knowledge of the Library and its collection. Nicholas Henderson, ambassador to Washington and Paris, commented: “He knew everything. You asked him anything you wanted to know and he knew where you would find it, he’d get you the book”. JW Lambert concurred: “I don’t know why this remarkable figure, portly, wheezing, wing-collared Mr Cox should have inspired such anxieties; I cannot remember any occasion when I received anything but benign, not to say patronizing, treatment at his hands – hands which had entered books for half the famous authors I had ever heard of.”

Cox died on 19th August 1952, and three days later the Times published a lengthy obituary. The newspaper described him as “a much loved and respected figure… a survivor of a bygone age of leisurely good manners…he needed little encouragement to draw on his memories of St James’s Square. It is not too much to say he became a sort of Remembrancer to all the members of the Library”.

Cox’s anecdotes – from fetching novels for Gladstone, gossiping about Thackeray’s mistress or dealing with the aftermath of Second World War bomb damage at the Library (“it wasn’t what we were used to”) – spanned a unique period in The Library’s growth and development. By his death he had established himself as one of London’s great characters, and if he had amassed a full store of memories, they were matched by those of countless Library members who had equally vivid memories of him!

In partnership with Jewish Book Week

Hampstead in the 1930s. Barbara Hepworth and Ben Nicholson have embarked on a love affair which will go on to launch an era-defining art movement.

Circles and Squares chronicles the exhilarating rise and fall of British Modernism, capturing the inner circle drawn into Hepworth and Nicholson’s wake: among them Henry Moore, Herbert Read, Paul Nash and the famed European emigrés Walter Gropius, Piet Mondrian and László and Lucia Moholy-Nagy. This enthralling, finely researched account threads together the lives, loves, ambitions and rivalries of the artists at the heart of an international avant-garde, trailblazers united in their belief that art could change the world. Author Caroline Maclean is in conversation with Lara Feigel.

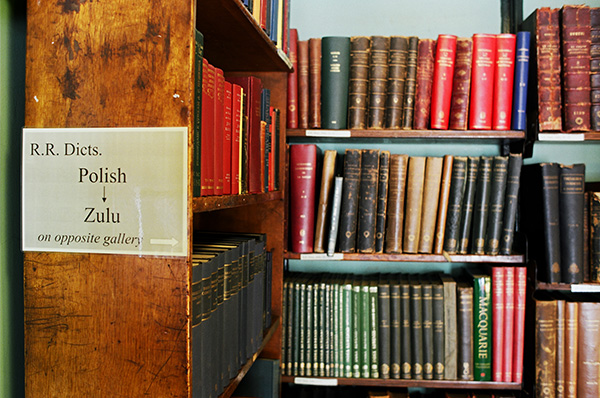

Those of you who find yourselves passing by the Library's window in Mason's Yard will have seen that a new display has been installed featuring new books by members, many of which have been written and researched in the Library.

The eclectic display showcases books from fiction, history, art and more - demonstrating the wide range of resources on offer to Library members.

It includes:

- Paul Laffan, The Fabricated Christ: confronting what we know about Jesus and the Gospels

- Mary Medawar, The Split Tree

- Michael Bond, Wayfinding: the art and science of how we find and lose our way

- David Beattie, Hans-Adam II

- Geoff Andrews, Agent Moliere

- Andrew Lycett, Conan Doyle's Wide World

- Hannah Rothschild, House of Trelawney

- Hugo Vickers, The Sphinx: the life of Gladys Deacon - Duchess of Marlborough

- Diana Devlin, Sam Wanamaker: A global performer

- David d'Avray, Papal Jurisprudence c. 400

- Sophy Roberts, Lost Pianos of Siberia

- Douglas Smith, Russian Job

- Andrew Alchin, Bvda, Ofen, pesto, Buda, Pest

- Diana Preston, Eight Days at Yalta: how Churchill, Roosevelt and Stalin shaped the post-war world

- Sophie Hardach, Confession with Blue Horses

- Alexandra Schulman, Clothes…and Other Things that Matter

- C. J. Schuler, Along the Amber Route : St Petersburg to Venice

- Judith Flanders, A Place for Everything : the curious history of alphabetical order

- Sinclair McKay, Dresden: the fire and the darkness

- Philip Hensher, A Small Revolution in Germany

- Simon Callow, London's Great Theatres

All of these books are now available to borrow from the Library, just log in to Catalyst to browse then choose to collect from the Library or have them posted to you at home.