Originally published in February 2014

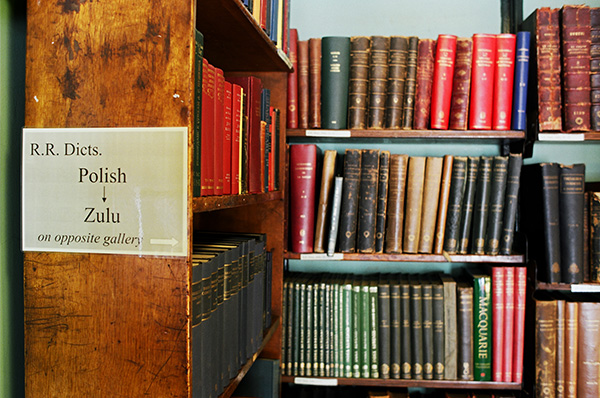

The Folklore collection at The London Library forms a substantial section in Science & Miscellaneous, with works from the 18th to the 21st century in English and many other languages. The universal subject of Folklore and its deeply rooted place in the cultural fabric of nationalities is reflected in the Library’s collections. The collection contains a wide range of works on different strands of folklore; traditional and popular beliefs, customs, legends, fairy tales and music.

Studies on King Arthur, the medieval and mythological figure can be found here, with works discussing the legend in its many guises; Merlin, the Holy Grail, King Arthur’s Knights and the Round Table. Some interesting works are: Arthur of Britain by E.K. Chambers (1927); La légende arthurienne: études et documents. Première partie, Les plus anciens textes by Edmond Faral (1929) and The Holy Grail, its legends and symbolism: an explanatory survey of their embodiment in romance literature and a critical study of the interpretations placed thereon by Arthur Edward Waite (1933). Interest on the legend is still as popular as ever, as recent acquisitions such as Worlds of Arthur: facts and fictions of the dark ages by Guy Halsall (2013) and The true history of Merlin the Magician by Anne Lawrence-Mathers (2012) suggest.

The major role of folklore collected and transcribed through oral tradition is seen in titles such as Tales of the fairies and of the ghost world’ collected from the oral tradition in South-west Munster by Jeremiah Curtin (1895) and Old Deccan days, or, Hindoo fairy legends current in southern India collected from oral tradition by M. Frere (1868).

Popular beliefs, traditions and tales are also included in works from abroad in the recently catalogued Curiosità popolari tradizionali series of books from different parts of Italy, and volumes in the series Les littératures populaires de toutes les nations include works from France, Greece, Turkey and China. Religious folklore is seen in Folk-lore of the Holy Land: Moslem, Christian and Jewish by J.E. Hanauer (1907).

The handed-down tradition of Folk music by unknown composers is seen in the folk songs of India, Greece, Serbia and Canada housed in the Library’s collections; Greek folk-songs from the Turkish provinces of Greece … Albania, Thessaly, (not yet wholly free,) and Macedonia: literal and metrical translations by Lucy M.J. Garnett (1885) are particularly note-worthy.

Fairy tales are a large part of the folklore section and probably the most well-known are Grimm’s fairy tales – Kinder- und Hausmärchen. Both early and current editions of the tales, including criticism, can be found here and have now all been retrospectively catalogued. In addition, some books on fairy tales from other parts of the world have also just been added such as: Welsh fairy-tales and other stories collected and edited by P.H. Emerson (1894); Chinese fairy tales told in English by Herbert A. Giles (1911) and Fairy folk tales of the Maori by James Cowan (1925).

The customs, superstitions and practices of subcultures are also explored. Sir James George Frazer’s famous work, The Golden Bough, a comparative study of mythology and religion (1890), includes such topics including a chapter on ‘Christmas and the mistletoe’, as does a more modern take on ‘superstition’, Old wives’ tales by Eric Maple (1981).

Other topics of interest found in the Library’s folklore collection retrospectively catalogued or soon to be, are books on moon mythology: Moon lore by Timothy Harley (1885); plant lore: La mythologie des plantes, ou, Les légendes du règne végétal by Angelo de Gubernatis (1878-1882) and The mystic mandrake by C.J.S. Thompson (1934); animal mythology: Un-natural history, or, Myths of ancient science: being a collection of curious tracts on the basilisk, unicorn, phoenix, behemoth or leviathan, dragon, giant spider, tarantula, chameleons, satyrs, homines caudati, &c. now first translated from the Latin, and edited, with notes and illustrations, by Edmund Goldsmid (1886); and werewolves: The werewolf by Montague Summers (1933).

The enduring popularity of Folklore influence is seen in the rise of contemporary fiction writing in this genre (notable in the Harry Potter series where mandrakes, unicorns, basilisks, dragons, phoenixes, giant spiders and werewolves feature), and is reflected in recent Library acquisitions Mythic thinking in twentieth-century Britain: meaning for modernity by Matthew Sterenberg (2013), The white devil: the werewolf in European culture by Matthew Beresford (2013) and The rise of the vampire by Erik Butler (2013).

Maame Blue and Sareeta Domingo, two of Jacaranda Books’ #TwentyIn2020 authors, discuss their stunning new novels, investigations of modern love and all its complexities.

Maame Blue's Bad Love is the story of London born Ghanaian Ekuah Danquah and her tumultuous experience with first love. Marked by this experience, she finds herself at a crossroads - can she fall in love again, or does the siren song of her first love still call?

Sareeta Domingo’s If I Don’t Have You is the story of Afro-Brazilian filmmaker Ren and Black British artist Kayla as they navigate their attraction to each other, alongside their carefully constructed lives and the secrets that lurk between them.

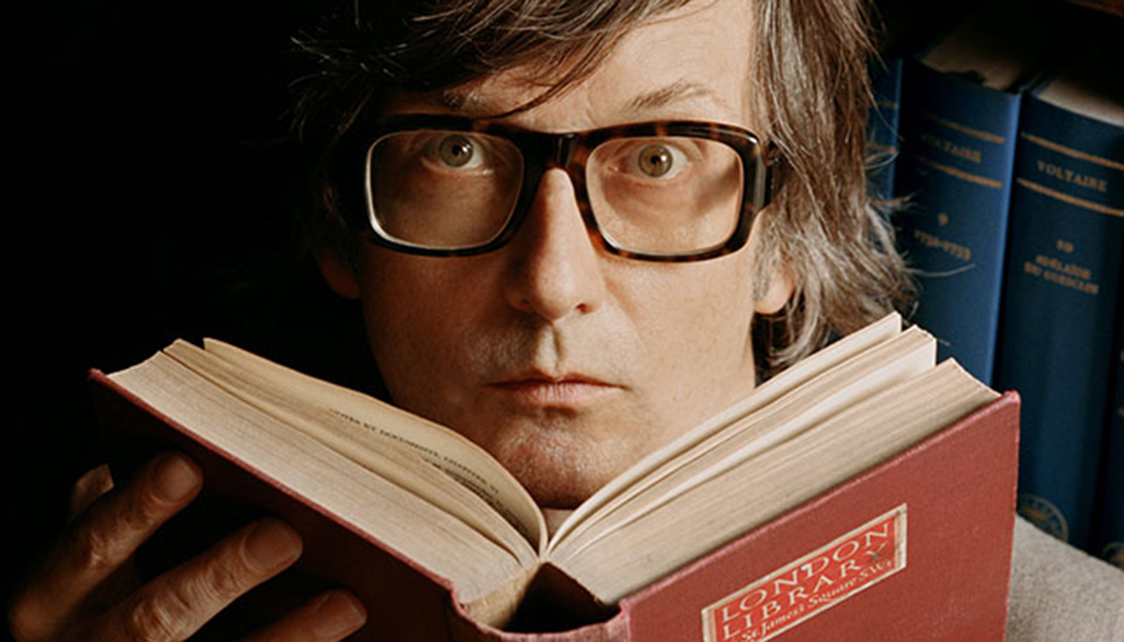

Thomas Carlyle (1795 –1881) was a writer, historian and philosopher. Born in Scotland, Carlyle moved to London in 1834 where he wrote, lectured and created a network of notable literary friends, including early London Library members such as JS Mill, Charles Dickens, Harriet Martineau, Leigh Hunt, WM Thackeray and Alfred Lord Tennyson.

In 1838, frustrated by the lack of a lending library in London, Carlyle began gathering support for the creation of The London Library. He was adept at articulating the need for such a resource and by April 1840 he had helped create a committee to pursue its foundation. In June 1840 the committee arranged a promotional event at the Freemasons Tavern, featuring speeches by various committee members, including Carlyle, who passionately elucidated the case for the Library to an enthusiastic audience.

The Library was founded in May 1841 and Carlyle sat on its first committee and was elected President in 1870.

As a writer, Carlyle produced some influential and highly celebrated works, including Sartor Resartus (1833-4), A History of the French Revolution (1837), and On Heroes, Hero-Worship, and The Heroic in History (1841). However, his later writings revealed his racist views. In particular, Carlyle’s essay Occasional Discourse on the Negro Question, first published anonymously in 1849, opposed the abolition of slavery. This bought him into direct conflict with liberal thinkers of the time including his erstwhile friend JS Mill who published an opposing essay. Carlyle’s racist views are completely unacceptable and the London Library does not share them.

The Library is a place for inspiration and support that is open and welcoming to all, regardless of race, ethnicity, religion, gender, sexual orientation, disability or age.

London’s parks, squares and gardens have played an important role over the last few weeks. It seems timely to remember and celebrate Thomas Hill, the Londoner responsible for the first popular gardening books printed in the English language.

Born around 1528, Hill appears to have been more of a literary entrepreneur than a true scholar. He himself confessed to have been ‘rudely taughte’ but he evidently knew enough Italian and Latin to select and translate the works of many classical authors. These translations formed the basis of Hill’s work and while some have accused him of not contributing new knowledge to the subjects he wrote on he did at least have enough of an understanding of these disciplines to choose his sources carefully, the necessary skill to render them into clear English and sufficient honesty to acknowledge in his book those whose works he compiled. He was also shrewd enough to pick popular subjects that would prove commercial successes: physiognomy, astrology, medicine, mathematics, almanacs, conjuring tricks, practical jokes, natural and supernatural phenomena and, of course, gardening.

His A Briefe Treatyse of Gardening was first printed without date probably around 1558 and was enormously popular, running to nine editions. Later editions were published under a different title, which spoke of the book’s success, The Profitable Arte of Gardening. It had been augmented by three appendices: The Mervailous Government, Propertie, and Benefite of Bees, With the Rare Secretes of the Honnie and Wax, The Yerely Coniectures Meete for Husbandmen and a Treatise of the Arte of Graffing and Planting of Trees. The London Library edition was printed in the capital in 1593 by Edward Allde, who at the time had his premises ‘in the Fore Street without Cripplegate at the Golden Cup’.

Thomas Hill’s star was rising when his life was cut relatively short in 1574. His second gardening book, The Gardeners Labyrinth: Containing a Discourse of the Gardeners Life, in the Yearly Travels to be Bestowed on his Plot of Earth, for the Use of a Garden … was printed posthumously in 1577.

Hill’s book lists herbs and vegetables giving first the ‘ordering, care and secrets’ and then ‘the physicke helpes’ or medicinal properties of each: ‘… parcely thrown into fish-ponds doth revive and strengthen the sick fish’, melon seeds ‘eaten or drunk doe cause urine, and purge the lungs and kidneis’. He also offers tips for getting rid of pests such as moles, characterised as ‘a disquiet and grief to gardeners’.

This second work includes many woodcuts, unlike his first book, making it much more expensive to produce and therefore increasing its retail price considerably, which must be a sign of how much Hill’s popularity had grown even after his death. It appears that his status had risen so much that he had even outgrown his name: on the title page Thomas Hill has grown into Dydymus (Greek for Thomas and literally meaning ‘twin’) Mountaine, a rather ridiculous pseudonym that must have nevertheless sounded grand and impressive to a 16th century book buyer. It would be fascinating to know whether this was done in accordance with Hill’s wishes or whether it was the printer’s idea for attracting a wealthier clientele. Either because of or in spite of the ‘mountaine’ effect, or rather because of the quality of the text and charming depictions of Elizabethan gardens, Hill’s second gardening book proved an even greater success than the first one and was reprinted many times. The London Library copy is dated 1586 and is the work of John Wolfe who had his workshop in Distaff Lane, near St. Paul’s.

When Hill died he left many completed manuscripts behind that were never published as well as some unfinished projects. One of the latter was a translation of Swiss naturalist Conrad Gesner’s The Newe Jewell of Health: Wherein is Contayned the Most Excellent Secretes of Phisicke and Philosophie. The translation was completed by his friend, the surgeon George Baker, and The London Library holds a copy of the beautifully illustrated first edition printed by Henrie Denham at the sign of the Star in Paternoster Row in 1576.

Read more: Making ‘Mountaines’ out of molehills – 16th century gardening books at The London Library