‘Dead Room’ - Mark Harris

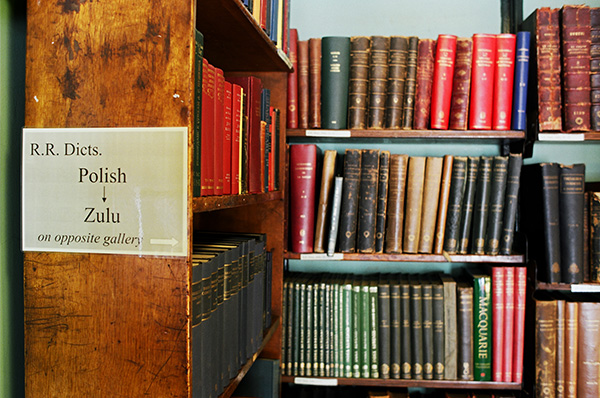

Over the past 12 months artists Mark Harris and Bob Matthews have been immersing themselves in the collection of The London Library. This month a number of striking artworks based on the images they have found, have gone on display in the Library.

They include three large scale works - Harris’ “Dead Room” and Matthews’ “Capsule” and “Talisman” - which can be found in the Periodicals stacks and Times Room. 15 smaller pieces can be found at various locations in the Central stacks, Back stacks and Art stacks (see map). The works - which have been produced free of charge to the Library as part of Bob and Mark’s artists’ residency - will be on display for most of 2020.

L: ‘La Houle’ - Mark Harris, R: ‘Elements of Editing 2’ - Mark Harris

Looking at the collection through the visual lens

During an intense period of research Mark and Bob developed methodologies for browsing, selecting and editing visual material, and as a consequence recorded 1000’s of images digitally. The act of collecting these images has helped them capture a unique pictorial world history spanning some 300 years. Their selection process would lead eventually to dozens of significant images to work from, creating inspiration for new artworks.

As printmaking specialists, Harris and Matthews were initially drawn to the way the Library’s collection reveals the history of the printed image. The collection holds significant examples of early engraving, etching and lithography, as well as more recent photographic printing techniques. This would lead to Harris producing Cyanotypes, an early direct photographic technique identified by its Prussian Blue appearance and ability to capture both photographic and autographic marks. Matthews technical research in the library would lead to the production of artworks using the photo-toxicity of lemons to aid the transfer of images.

‘Capsule’ - Bob Matthews

Within the Library the Periodicals section was an area that revealed many images of interests, from the 18th Century Journals of Italian Letters through to the collection of BBC Handbooks. Both artists were drawn to the idea of making site-specific artworks for the Periodicals space that would bring together a number of ideas from their research across the library. They have produced large scale pieces that are revealed through the movement of the shelving mechanism, echoing the action of a printing press. This deliberate obstructive presentation of the work refers to the many folded pages of images and diagrams that they discovered.

Additionally, across 3 levels of the Central Stacks Harris has produced a series entitled Elements of Editing that comment on the joint industrial journey that both materials and images take, as they are mined and captured, refined and edited, produced and published. Other artwork is situated throughout the Back Stacks.

‘As it Might Be...’ - Mark Harris

Bob Matthews and Mark Harris commented, “It has been an enriching and fascinating experience exploring the visual material held within the Library. We hope that the work will suggest alternative ways to access the collection and that we have sewn a seed for many more potential future projects between The London Library and the visual arts.”

(Left: George Gilbert Scott; Top: Sir Gilbert Scott's membership form from 1873, he was introduced to the Library by his son, George Gilbert Scott Jr; Bottom: George Gilbert Scott Jr an architect and scholar joined the Library in 1872. He was introduced by fellow member, architect Thomas Garner.)

We take a look at the links between The London Library and a distinguished architectural dynasty founded by Sir George Gilbert Scott, the leading proponent of the Gothic Revival.

In London’s swinging sixties, the poet, broadcaster and co-founder of The Victorian Society, John Betjeman, took a stand against the destruction of Britain’s Victorian architectural heritage. After the demolition of Euston Station’s Doric arch, he campaigned to save another iconic Victorian landmark: the Midland Grand Hotel at St Pancras station, as it too tottered on the edge of demolition. It was a building, he said, Londoners enjoyed: a “sudden burst of exuberant Gothic … seen from gloomy Judd Street.”[i]

The hotel was the creation of Sir George Gilbert Scott (1811-1878), the founder of a dynasty of architects which continues today and which stretches from The Midland Hotel “the grandest single monument of the Gothic Revival in Britain”[ii] to the power stations at Battersea “one of the first examples in England of frankly contemporary industrial architecture”[iii] and Bankside (now Tate Modern) taking in the Albert Memorial, Waterloo Bridge, the red telephone box and a staggering number of churches and cathedrals en route.

Sir George Gilbert Scott and his son, George Gilbert Scott Jr (1839-1897) both appear in the Victorian membership records of the Library. George Gilbert Scott Jr joined in 1872 and introduced his father (who was knighted in 1872 and President of RIBA 1873-76) to membership in 1873. Sir George Gilbert Scott’s Personal and Professional Recollections, edited by his son, appeared in 1879: one of the first autobiographies of an architect to be published.

While Sir George Gilbert Scott was an acclaimed Victorian architect, who ran one of the largest architectural practices in Europe, he was not without critics – several of whom are also to be found among the membership records of the Library. The Rev W.J.L. Loftie, the architect J.J. Stevenson and one of the founders of the Arts and Crafts Movement in Britain, William Morris, all articulated a growing unease about architectural restoration, which John Ruskin condemned as a lie declining a RIBA gold medal during Scott’s presidency.

George Gilbert Scott Jr struggled throughout his life with mental health issues and alcoholism. He was confined to Bethlehem Hospital in 1883 and spent several years in and out of hospital. He died of cirrhosis of the liver and heart disease in1897. He was living at the time in his father’s famous secular creation: the Midland Grand Hotel (now renamed the St Pancras Renaissance Hotel). While his professional life was less prolific than his father, his own son, Sir Giles Gilbert Scott (1880-1960) an influential 20th century architect, considered that “Grandfather was the successful practical man, and a phenomenal scholar in Gothic precedent, but Father was the artist”.

Neither Sir George Gilbert Scott nor his son lived long enough to see the unveiling of the London Library’s Victorian steel grilled book stacks, circulating hall or spacious 50 ft long Reading Room in 1898. These Victorian spaces however remain at the heart of the Library’s activities today. Architectural heritage is easy to spot, it connects our physical environment and our daily lives to the past. Betjeman was right about the Midland Grand Hotel which was given Grade 1 listing in 1967. The Victorian Back Stacks of the London Library are also a listed structure, like the Midland Grand Hotel they too exert a powerful burst of Victorian Gothic in the hustle and bustle of 21st century London Library life.

Read more: The Victorians & The London Library: The George Gilbert Scotts

Michael Billington: The End of Theatre Censorship at The London Library

Celebrating the 50th anniversary of the Theatres Act 1968 Michael Billington chairs a panel of experts looking at the history of theatre censorship dating back to the Licensing Act 1737 and debating different types of censorship that exist in theatre today.

Read more: Michael Billington: The End of Theatre Censorship

There was no more sensational trial or public fall from grace in the Victorian era than that of the writer, playwright and cultural icon, Oscar Wilde. Secreted in the Library’s Victorian membership ledgers are the names of Oscar Wilde’s wife, Constance; his publishers John Lane and Algernon Marshall Methuen; and his illustrator Aubrey Beardsley. Constance appears in the Library’s membership records in 1894 giving her occupation or position as “Wife of Oscar Wilde Esq”. Within a year of joining the Library her husband was serving a two year prison sentence with hard labour and the family home at Tite Street, along with all its contents, had been auctioned off.

Wilde’s iconic fin-de-siècle illustrator Aubrey Beardsley joined the Library in 1896 when he was twenty-three. His risqué illustrations for Wilde’s illustrated edition of Salome were commissioned when Beardsley was just twenty-one and caused a scandal on publication. Wilde dedicated Salome to “My Friend Lord Alfred Bruce Douglas” and the play was published by another London Library member, John Lane with his business partner Elkin Matthews. Beardsley’s art is stamped on the short-lived but influential avant-garde magazine The Yellow Book, which was also published by John Lane at the Bodley Head between 1894 and 1897. The Yellow Book became inaccurately but fatally associated with the scandal that surrounded Wilde when the press reported that he had a “yellow” book under his arm when he was arrested at the Cadogan Hotel in 1895. In a bid to distance Bodley Head from the furore John Lane swiftly ceased publication of the magazine, withdrew Wilde’s plays from publication and sacked Beardsley.

It was another London Library member, Algernon Methuen Marshall Methuen, who first published part of De Profundis in 1905: it was a book which triggered the start of Wilde’s literary rehabilitation. A first edition was quickly acquired by the Library in February 1905. In the form of a letter to Lord Alfred Bruce Douglas, it is a composition of some 55,000 words written during Wilde’s incarceration. It became, on first publication an instant best seller. 10,000 copies were sold within a few weeks and 14 editions followed over the next three years. In 1962 while he was Chair of the Library’s committee, the writer and publisher, Rupert Hart Davis published an authoritative edition of The Letters of Oscar Wilde which included, what is considered to be, the first true text of De Profundis.

Alongside a first English edition of De Profundis, the Library has a very rare German edition of the work which was published in Berlin in 1905 by S. Fischer. Bound in vellum on handmade paper with gilt lettering on the spine, it is one of only twenty such copies made. What makes it noteworthy is not only the quality of its production but the speed at which the Library acquired it. Published in Germany in 1905 it was available for loan from the Library’s shelves by July the following year – and there it has remained ever since.

Wilde’s vulnerability is present in an exceptional first edition in the Library’s collections of The Ballad of Reading Goal by C.3.3. Written after Wilde’s release from prison, it was published in London by Leonard Smithers in 1898. It is lightly inscribed in ink manuscript on the front flyleaf by Wilde, at that point an exile in Paris. It is addressed to his publisher Leonard Smithers “in gratitude and wonder”. Tipped in at the back of the book is a letter from Smithers explaining Wilde’s inscription. Dated 27 January 1898 it reads:

‘This copy of “The Ballad of Reading Gaol” (No 1 of thirty copies on Japanese vellum) was given to me by the author. The inscription “In gratitude and wonder” I presume means, in gratitude for my having produced his book; and wonder at my having done so, when other London publishers refused.’

After his release from prison Wilde wrote two letters to the editor of the Daily Chronicle about the need for prison reform. The letters were reproduced in pamphlet form in 1898 by Murdoch and Co. and sold for a penny. In Children in Prison and Other Cruelties of Prison Life Wilde describes the dehumanizing effect of the prison system on all who came into contact with it. He made a direct request for the case of prisoner A.2.11 (a young soldier whose inhumane treatment Wilde witnessed at first hand) to be looked into as a matter of urgency. He also praised the kindness of a prison warder named Martin, whom he knew from his time in Reading, who had been sacked for acts of humanity–in particular for giving sweet biscuits to a tiny, hungry child.

As Wilde prepared to leave prison he wrote “I know that on the day of my release I shall be merely passing from one prison into another…Still I do see a sort of possible goal towards which, through art, I may progress … On the other side of the prison wall there are some poor black soot-besmirched trees which are just breaking out into buds of an almost shrill green. I know quite well what they are going through. They are finding expression.”

Read more: The Wilde Side: Oscar Wilde and The London Library