50 years since the death of E. M. Forster, one of our greatest novelists, we pay tribute to his ground-breaking literary output and his love for The London Library, of which he was a member for 64 years.

In these videos, novelist Abi Daré reads from Forster’s tribute to the Library on its centenary; publisher and Forster biographer Nicola Beauman celebrates Where Angels Fear to Tread as the first modern novel; journalist and historian Kavita Puri explores Forster’s insight into colonialism in A Passage to India; and novelist Philip Hensher discusses Maurice, Forster’s controversial depiction of homosexual life, which wasn’t published until after his death.

Edward Morgan Forster was a novelist, short story writer, essayist and librettist. His first novel was Where Angels Fear to Tread (1905). Three novels followed in short order - The Longest Journey (1907), A Room with a View (1908) and Howards End (1910), establishing Forster, still in his early thirties, as an author of international renown. His greatest success came with A Passage to India - the last novel he was to publish in his lifetime - which appeared in 1924. Maurice, was published posthumously in 1971.

Joining the Library in 1906, he was one of the most important literary names of his day and was nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature on no fewer than 16 occasions. His books have been adapted multiple times into films and television series to great success. He died on 7 June 1970, aged 91.

Abi Daré reads from E M Forster’s tribute to The London Library in the New Statesman and Nation (1941).

Abi Daré grew up in Lagos, Nigeria and has lived in the UK for eighteen years. Her debut novel, The Girl with the Louding Voice, won The Bath Novel Award for unpublished manuscripts, was a finalist in The Literary Consultancy Pen Factor competition in 2018 and has been shortlisted for the Desmond Elliott Prize 2020. In 2019 she was selected for the London Library Emerging Writers Programme.

Nicola Beauman on Where Angels Fear to Tread (1905)

Nicola Beauman is the author of A Very Great Profession: The Woman’s Novel 1914-39, Cynthia Asquith, The Other Elizabeth Taylor and Morgan: a biography of EM Forster in 1993. She is the founder and publisher of Persephone Books, which was set up to reprint (mostly) women writers, (mostly) of the inter-war period and now has over a hundred titles in print.

Kavita Puri on A Passage to India (1924)

Kavita Puri works in BBC Current Affairs and is an award-winning TV executive producer and radio broadcaster. Her critically acclaimed Radio 4 series, Three Pounds in My Pocket, charts the social history of British South Asians from the post-war years. Her recent book and Radio 4 documentary series Partition Voices is the history of the partition of India through the first hand testimonies of witnesses now living in Britain.

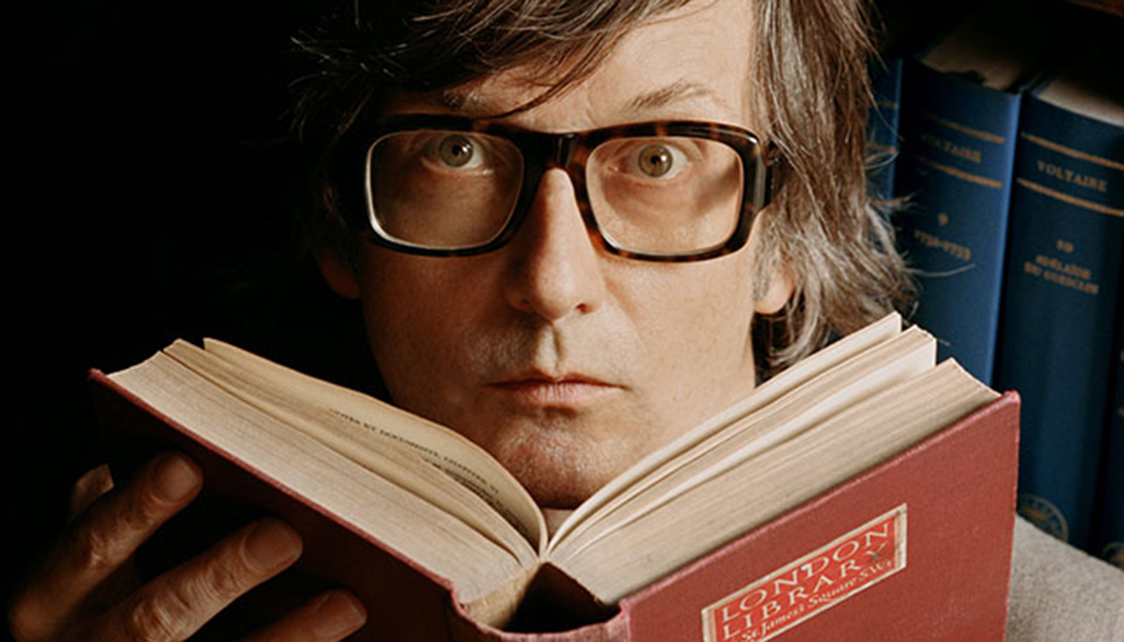

Philip Hensher on Maurice (1971)

Philip Hensher is an award-winning novelist, journalist and Professor of Creative Writing at Bath Spa University. He edited The Penguin Book of British Short Story, Volumes 1 and 2 and his novels include The Mulberry Empire, The Northern Clemency, Scenes from Early Life, and A Small Revolution in Germany, which was published this year. He writes for the Independent, the Mail on Sunday and the Spectator, amongst other publications.

As we commemorate the legacy of Charles Dickens - who died 150 years ago on 9th June 1870 - we’ve been digging through the archives, finding some of the remarkable associations Dickens and his close circle had with the Library in its early years.

Dickens was a Founder Member of the Library - one of the 500 who in 1840 answered Thomas Carlyle’s call to help fund a lending library in the capital. By that time he was emerging as a major literary name, having written five bestsellers in book and serial form in the space of just four years - Sketches by Boz (1836), Pickwick Papers(1836-37), Oliver Twist (1837-39), Nicholas Nickleby (1838-39) and The Old Curiosity Shop (1840-41). His name appears on the Committee running the Library between 1846-47 and he may well have been a full Committee member before that.

What may have spurred Dickens’ involvement in the early story of the Library is the fact that among the 528 Founder Members are some of his closest friends and associates, including perhaps the most important person in Dickens’ life - John Forster.

John Forster

Forster was Dickens’ lifelong friend, a major influence throughout his career and godparent to Dickens’s first daughter. He was also central to the Library’s foundation, devising and promoting the original subscription scheme and working tirelessly as one of the original Committee members running the Library when it was first established.

Forster’s literary importance was built on his role as Literary Editor (and subsequently Editor) at The Examiner. It was there, in 1835, when he first met Dickens (as serialisations of Sketches by Boz were beginning to appear) and he rapidly assumed the role of Dickens’ unofficial business manager, negotiating publishing contracts, advising on plots (the death of Little Nell was at his suggestion) and reading all Dickens’ proofs. In later years, Forster wrote a major biography of Dickens and claimed that, “There was nothing written by him... which I did not see before the world did, either in manuscript or proof”.

William Macready

William Macready is another of Dickens’ close associates who joined the Library as a Founder Member. The 44 year old actor was first introduced to the 25 year old author in 1837 by John Forster after a theatre performance in Covent Garden. The pair became firm friends. Nicholas Nickleby (1838) was dedicated to Macready who became godparent to Dickens’ third child the following year. Macready then had a key role to play in the Dickens’ family in 1842, helping look after their three children when Dickens and his wife Catherine went on a gruelling six month tour of the USA.

George Cattermole

George Cattermole was the illustrator of The Old Curiosity Shop and Barnaby Rudge which were published in book form in 1841 and 1842 respectively. Cattermole worked closely with Dickens throughout 1840-41 when these works were being serialised in instalments in the Dickens publication Master Humphrey’s Clock. During that period Cattermole joined The London Library as a Founder Member.

Daniel Maclise

Painter Daniel Maclise also became a London Library Founder Member in 1840. He had been a firm friend of Dickens and Forster since the late 1830s and in 1839 painted one of the most famous of the known Dickens portraits (shown above) - commissioned by Chapman & Hall and exhibited to acclaim at the Royal Academy in 1840.

Thomas Carlyle

The Library’s founder Thomas Carlyle had made his name with the publication of The History of the French Revolution in 1837. Dickens first met Carlyle at a dinner given three years later, when Carlyle was first hatching his Library plans. The pair admired each others’ work and shared social circles, not least because Carlyle was also a close friend of John Forster. Dickens dedicated Hard Times (1854) to Carlyle and A Tale of Two Cities (1859) was inspired by Carlyle’s History of the French Revolution. Indeed, it was partly researched under Carlyle’s guidance - Carlyle personally selected a number of London Library books on the French Revolution and sent them over to Dickens’ house in a cart. It is very likely that several books we still have on our shelves - and which have been there since the day the Library first opened its doors - were among them.

Thomas Talfourd MP

Dickens dedicated Pickwick Papers to Thomas Talfourd in 1837 having been introduced to the Liberal MP earlier that year by John Forster. Talfourd is another member of the Dickens/Forster circle who joined the Library as a Founder Member in 1840.

Edward Chapman and William Hall

From 1837, alongside his role as Literary Editor on The Examiner and Dickens’ unofficial business manager - John Forster also worked as chief literary adviser for publisher Chapman & Hall. Chapman and Hall had signed up Dickens for early sketches for Pickwick Papers the year before and would remain his publisher for over 20 years, publishing most of his works during that period. Edward Chapman and William Hall both joined The London Library as Founder Members in 1840.

Carlyle’s vision of a lending library in London came to fruition through the dedication and support of a group of figures whose early commitment helped the Library open its doors on 3rd May 1841. The list of those Founder Members shows that Charles Dickens and his most intimate circle - with John Forster at the centre of it - were a vital part of that story.

This year marks the 50th anniversary of EM Forster who died on 7th June 1970 aged 91.

Forster was a London Library member for 64 years, having been given life membership by his aunt in 1906, the year after the publication of his first novel Where Angels Fear to Tread. Three novels followed in short order - The Longest Journey (1907), A Room with a View (1908) and Howards End (1910), establishing Forster, still in his early thirties, as an author of international renown. His greatest success came with A Passage to India - the last novel he was to publish in his lifetime - which appeared in 1924 (a fifth novel, Maurice, was published posthumously in 1971).

Although his novel-writing career finished remarkably early, his reputation as a literary figure was enormous. A frequent commentator, essayist, short story writer and broadcaster, he was one of the most important literary names of his day. He wrote the libretto for Benjamin Britten’s Billy Budd and was nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature on no fewer than 16 occasions.

He was also a highly involved member of The London Library. We see him actively bringing new members to the Library - in 1920, he nominated Siegfried Sassoon for Library membership. In 1943 it was the turn of actor Robert Donat, best known as the star of the 1939 film Goodbye Mr Chips. Forster was a Committee Member of the Library throughout the war and in 1961 became Vice-President. He also had a significant part to play in saving the Library from bankruptcy, donating the manuscript of A Passage to India to raise funds at auction in 1960. It sold for £6,500 - the highest price that had ever been paid for a manuscript from a living author.

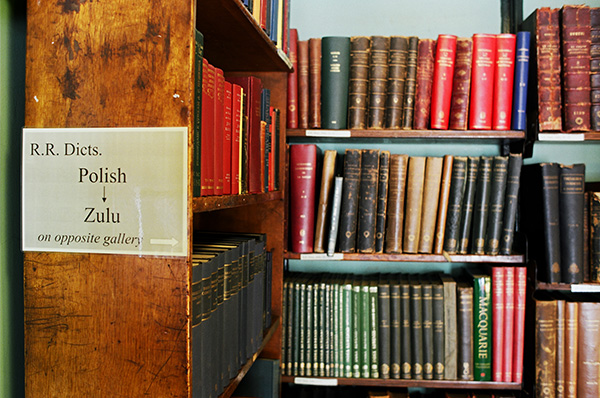

Almost the last sighting of Forster at the Library comes from author Susan Hill. Her book Howards End is On the Landing (2009) records an encounter with an elderly gentlemen in the stacks in the late 1960s when Hill was an undergraduate. It was Forster, still browsing in the Library he loved - dropping the book he was gathering on Hill’s foot as he made way for her.

And Forster clearly did love the Library. Commemorating its centenary during the height of the Bitz in 1941, Forster wrote evocatively in the New Statesman and Nation. “Buildings are in heaps, the earth is in holes. Safe still among the reefs of rubbish, the Library seems to be something more than a collection of books. It is a symbol of civilization. It is a reminder of sanity and a promise of sanity to come.”

He saw it as a redoubt in a troubled word. The Library “has cherished the things of the mind, it has insisted on including all points of view. It caters ... for creatures who are trying to be human. The desire to know more, the desire to feel more, and accompanying these, but not strangling them, the desire to help others: here briefly is the human aim, and the Library exists to further it”.

Undocumented Online Event Video

Kamila Shamsie speaks to authors Nikita Lalwani and Abi Daré about their stunning new novels, telling the stories we never hear about the people we never see.

Lalwani’s, You People, is set in a London pizzeria staffed by illegal Sri Lankan immigrants and presided over by the mysterious Tuli, a resident Robin Hood, who promises to help anyone in need.

Daré’s The Girl with the Louding Voice is the story of Adunni, a young Nigerian woman sold into domestic servitude but determined to find her voice.

Asking difficult moral questions, these novels cast their light on the people who live in the shadows: the asylum seekers and illegal immigrants, the enslaved, the disenfranchised and the undocumented, who silently and thanklessly underpin economies and maintain lifestyles from London to Lagos and everywhere in between.