During the Library’s closure period all requests are being fulfilled by post. A small number of staff are on site twice a week in order to retrieve and send items. However, there are likely to be delays in supplying books as there is heavy demand for the service and we are aware that the postal service nationally is under great pressure. As a result, a book may appear on your account several days before it is delivered. Items from our Special Collections or any that require a guarantee form will not be supplied during the closure period.

As you will understand, demand for this service is very high and the staff are working in a very structured way for their own safety. As a result, once a book has been requested, we will be unable to identify it and cancel the hold should you change your mind.

If you would like the book to be sent to an address other than the one you have registered with the Library (see My Account for the address we hold) please email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. to update your address before placing the holds. We cannot guarantee that the book will go to the correct address if you let us know after the request has been placed.

Members are able to return books to us either by post to our Mason's Yard address or through the letterbox at our St James's Square entrance.

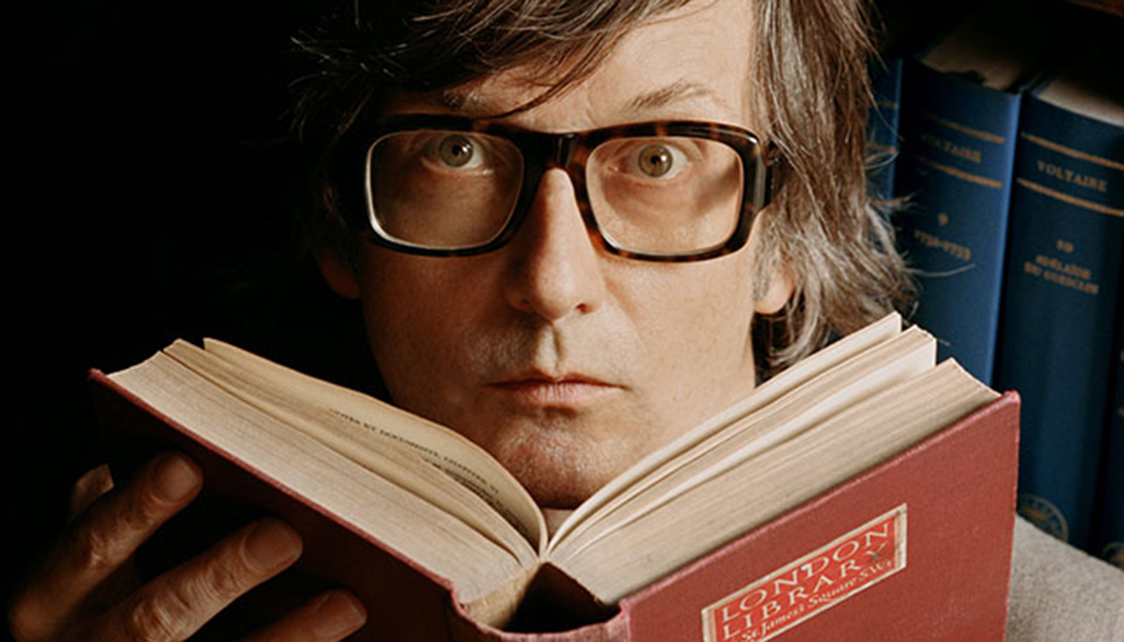

Harriet Evans

We are delighted to be joined by London Library member and Sunday Times Top Ten bestselling author, Harriet Evans.

Harriet's book choices include: The Lion, The Witch and The Wardrobe by CS Lewis; The Secret Diary of Adrian Mole, Aged 13 ¾ by Sue Townsend, The Light Years by Elizabeth Jane Howard and I Capture the Castle by Dodie Smith.

The Art of Persuasion: Benet Brandreth on Rhetoric

In this entertaining hour, expert Benet Brandreth QC introduces us to the fundamentals of classical rhetoric and shows us how the techniques of Cicero and Shakespeare are still being put into practice by modern politicians the world over.

Read more: The Art of Persuasion: Benet Brandreth on Rhetoric

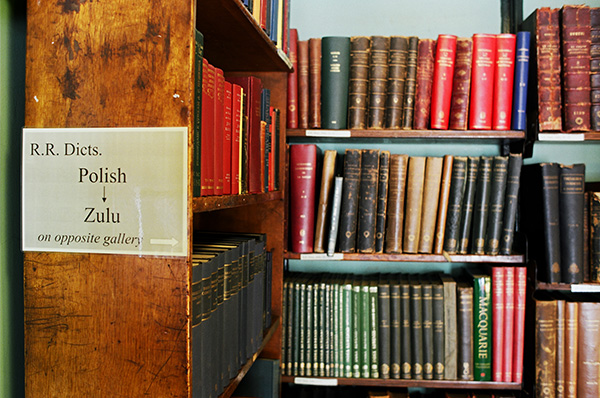

Back in 2015, Radio 4’s Broadcasting House decided to find out more about the appeal of miniature books and presenter Paddy O’Connell came into The London Library to explore a selection of some of The London Library’s collection of small and miniature books. In a fascinating interview, Helen O’Neill, our then Archive, Heritage & Development Librarian, introduced some of its highlights.

The collection contains nearly 350 small books printed between the 16th and the 20th centuries, and measuring up to five inches tall. This includes several early Bibles, the beautifully illustrated A Simple Story by Elizabeth Inchbold (published in 1840), 1927 collections of James Joyce’s poems; and one of our earliest small books printed in 1515 by Aldus Manutius, the originator of the printed pocket book and the inventor of the space-saving italic typeface.

Even smaller, but equally eye-catching, are seven miniatures (defined as books under three inches tall), printed mostly in the 19th century, the golden age of miniature printing. Among these is the smallest version of Dante’s Divina Commedia in the world, the legendary ‘fly’s eye Dante’ of 1878. The Library also holds the smallest Authorized Version of the Bible, printed by David Bryce of Glasgow in 1896 which comes complete with its own magnifying glass. Among the childrens’ books in this collection a miniature edition of Kate Greenaway’s Alphabet from the 1880s stands out.

Small books often presented a showcase for the latest technology of each era where masters of printing and typography sought to display their skills and some of the craftsmanship on display on the small and miniature books collection is breathtaking. But the collection also casts an interesting light on the history of the print industry; particularly how mass manufacture and consumption led to the use of cheap materials in many small books. Chapbooks, for example, were disposable and so extant copies of these single sheet, paper wrapped ephemera are few. The Library holds a number of rare survivals of this type – for example Louis Janet’s Le Petit Sorcier, (part of a set of ‘almanachs microscopiques’ used as promotional materials for 18th century Paris shops); or the scandalous Friponniana, Gascogniana, and Grivoisiana which Simon Blocquet published from Lille in the early 19th century. A significant 20th century volume is Sali͡ut, a unique set of 18 children’s booklets printed in Moscow by Detgiz in 1944. Bound together they have survived the instability of the paper and prove a rare insight into Stalin era propaganda.

Much of our small and miniature book collection is housed in the familiar cabinet adjacent to the Reading Room. They reward further examination and as Broadcasting House presenter Paddy O’Connell describes are “a feast for the eyes” – even if you need a magnifying glass to appreciate them fully!

Left: The smallest authorised Bible in the English language containing the Old and New Testaments was published in Glasgow by David Bryce & Son in 1896. A feat of printing and binding craftsmanship, it came with its own magnifying glass.

Centre: Known as the “Fly’s Eye Dante” or “Dantino” this is the smallest edition of the La divina commedia. It was published in Milan by Ulrico Hoepli in 1878. It is thought to be the smallest type at the time of printing which injured the eyesight of both the compositor and corrector in its production. It took one month to print 30 pages.

Right: Small sizes lend themselves to small hands as Kate Greenaway’s Alphabet shows. Published in London by Routledge in 1885 it is in remarkably fine condition for a children’s book.

Left: Theodore Botrel’s Chansons et Poesies was published in Paris by Paysan in 1917. It measures 10cm in height and is bound in fabric. Botrel was a singer, songwriter and playwright who visited French troops at the Front during the First World War to sing and read poetry.

Centre: This highly decorative edition of Elizabeth Inchbold’s A Simple Story was published in London by Charles Daly in 1840. Inchbold was a famous actress, playwright and novelist and this edition of her Simple Story, though highly decorative, had a female central character that challenged authority.

Right: In 1927, five years after the appearance of Joyce’s modernist masterpiece Ulysses, his publisher, Shakespeare and Co issued this small collection of Joyce’s poems in Paris. The volumes measure just 13cm in height and the Library acquired two editions in the year it was published.