You may have seen stories we ran on social media recently about two of the world’s most famous actors - Alec Guinness and Paul Robeson.

It turns out that both were members of The London Library, and we are delighted to have recently discovered their membership forms.

Our archive reveals that Paul Robeson joined in February 1934 and his membership was nominated by the acclaimed writer Rebecca West, who Robeson first met in 1925. West - who eventually became a Library Vice-President - remained a friend and firm supporter of Robeson’s celebrated political activism and accompanied him during a famous speech he gave in 1937 attacking fascism.

Alec Guinness joined the Library in 1957 and he remained a member here for over 30 years. His membership was nominated by no less a figure than Daphne du Maurier. Guinness had just started work on Scapegoat - the 1959 film based on du Maurier’s novel of the same name (Du Maurier later claimed that Guinness had been miscast in the role!).

It’s fascinating to see these figures connecting with the Library and we’ll bring you more exciting archive discoveries in future issues.

Please see the Collection Strategy Implementation page for background and context to the FAQs below.

1. De-duplication of books

Q: Does the Library treat different editions of books as duplicates?

A: No – the definition of ‘duplicate’ as it applies to our collection management means identical copies of the same edition, although there may be occasional decisions made by senior staff where there are multiple editions with no discernible usage at all taking up significant space on the shelves and these come to our attention through the duplicates work.

Q: How does the Library measure usage of stock to decide that multiple copies are no longer required?

A: Duplicates work has a formula to work to which looks at the date labels of all copies (and editions) over a set period of time. It allows for the full loan period and some renewals.

-

2. Removal of print holdings where digitised versions or free access to other print copies are available

Q: Does the Library check holdings in other libraries when it is considering withdrawing stock, or carrying out other collection management work?

A: Yes, the staff check for holdings of other print copies, in libraries that members can access. The emphasis on any work on withdrawing stock is on minimising loss of access to content, and the process is carried out very carefully.

Q: How does the Library measure usage of stock and decide that something is of ‘lower use’?

A: Circulation statistics (issues and returns) are a key way to decide if something has seen lower-use, but such data is used as a starting point only to identify likely low-use material for further consideration. Many more checks are done at the shelf to assess usage and importance of items to the collection, and how they complement other holdings. There are, however, a numbers of areas of the collection where the lack of loans is not necessarily an indication that the title is not being used. Examples are bound volumes of periodicals or large art titles. In order to capture as much of this usage as possible the Library registers ‘in-house’ use, by scanning items left by members for reshelving. This data is recorded on the item’s record and can be used to assess whether an item is being consulted in the Library rather than borrowed and taken home.

Q: With regard to relying on online versions of material, such as journals, what does the Library mean by ‘robust and stable sources’?

A: There are a number of subscriptions to online content that are considered as core to our content provision as the purchase of new material; JSTOR is a particular example for journal archives and British History Online is invaluable for state papers and other historical documents although it is still a work in progress re the digitising of these primary documents. We retain print copies of non-digitised material. We also subscribe to a number of commercial or academic suppliers of digitised material for current content. There is also a wealth of what we regard as ‘stable’ sources which are external and freely available, such as Gallica at the Bibliotheque Nationale, a number of German university sites offering digitised materials as well as hansard.parliament.uk which provides verbatim reports of the proceedings in both Houses. Material that is out of copyright may often be found on the Internet Archive project as well as other more specialist sites.

-

3. Off-site storage

Q: Is it economical to hold low-use material off-site?

A: Off-site storage is not cheap, but is a preferable alternative, if funds can be found, to extensive withdrawal of stock involving significant loss of content, or a reduction in the purchase of new material. The Library has to consider the pros and cons of what to move to off-site store very carefully, and decide whether The London Library is the right institution, and is acting responsibly with regard to its limited funds, in storing material that may be accessible through other institutions such as local university libraries like the LSE and the British Library.

Questions we consider include whether a title is:

- Held onsite at other libraries in London

- Available through inter-library loan

- Available online

- Out of scope of the Library’s collection, for instance not fitting within, or complementing, the Library’s collection strengths

Q: What will be the turn-around time for requests for material from off-site store?

A: We are still investigating the best options for our storage provider, and also engaging with HE libraries over any potential collaborative stores which may also make additional content available to members. The service provision is an important part of our considerations, but we would hope to work with a provider who can supply material within a 48-72 hour window or possibly even post titles directly to the requestor.

-

4. Withdrawn stock

Q: What happens to withdrawn stock?

A: Stock that is in good enough condition to offer to others is passed to the trade from whom we obtain good prices. Some members have asked whether books can be offered for sale to members, and this is under consideration although the logistics of managing this are considerable. Long runs of series publications that are available online are very difficult to move on to the trade as there is very little interest in these due to their size and weight and accessibility online. Every effort is made to offer these to other libraries and the trade but they will be disposed of if none of these avenues proves fruitful. Disposal has become standard practise in university libraries as markets will have been flooded early on when the move from print to digital started.

Q: What is the timescale for the completion of the cataloguing of all outstanding stock?

A: There is a project underway to assess how this can be accelerated to facilitate better discovery for members and those outside the Library, as well as to make it easier to move stock to off-site store and have it retrievable. Subject to fundraising, the hope is that this project could be completed within 2-3 years, making an additional c.45,000 items findable through the on-line catalogue.

Proposed next steps

The proposed strategy is to withdraw from the collection some journal and government publication material that is available online; foreign language journal material that has ceased acquisition; obsolete material; and duplicate copies of books where these are not warranted. Additionally, the proposal is to begin a strategy to move some low-use books to off-site store, with selected foreign language works in subjects other than literature, history and art identified as a particularly low-use category with which to start.

Some drop-in sessions were held with members in January which yielded very useful feedback on the proposals, and brought many other points forward for discussion. There will be further engagement with members as the Library continues to work through its proposals, all of which are given extremely careful thought.

The following steps are proposed in our on-going collection management work:

- Foreign government publications (primarily Indian and US (75 linear metres each) plus assorted short amounts of others) – no objections were raised to their removal in the drop-in sessions with members, and no reason for these to be stored off-site was raised.

Action: Subject to some final checking, move forward with removal.

- Duplicate copies of books – all members saw sense in de-duplicating multiple copies of books and no objections were raised.

Action: Progress with the removal of duplicate copies of books.

- Bibliography – there was useful discussion over the reference use of this collection, with some concerns raised that our usage indicators wouldn’t pick this up. There was also some concern expressed over the markings-up in place in this collection.

Action: Engage further with members to gain more views before deciding on a strategy for this collection.

- Parliamentary papers – implement project to create an electronic listing of the indexes and postpone decision as to whether to move the collection off-site until investigative work can be carried out into their uniqueness in print from in the London area.

Action: carry out data entry work.

- Short, incomplete journal holdings in all languages.

Action: Continue close investigation into these for content/relevance/reasons to keep;

- Journal material available on JSTOR and other stable, robust subscriptions –

Action: Continue checks on other holdings and at-shelf work to identify journals with significant reliance on illustrations which may be inferior in the online version. In parallel, phase subject-based listings for members on our webpages of titles for removal and for retention off-site and seek feedback.

- Books in foreign languages

Useful discussion was had around foreign language holdings. The Library proposed looking at books in foreign language where the language didn’t pertain to the content of the book, and members asked for a greater understanding of what is meant by these.

Additionally, members made further suggestions of their own relating to foreign language holdings, including:

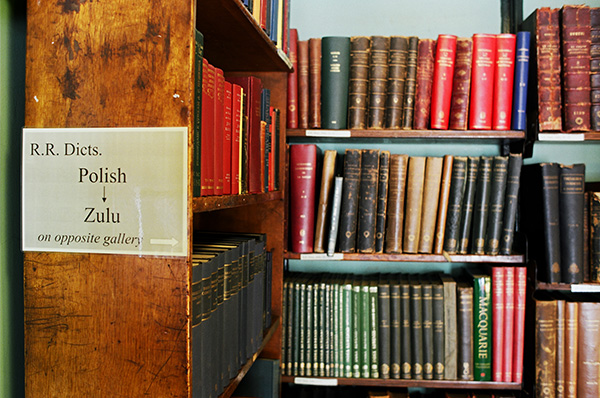

- Remove books in languages less used by members – Polish was given as an example – noting that less space will be gained through the removal of smaller collections;

- Consider where works are held in English translations as well as the original, and usage is noticeably higher in translation;

- Identify a greater range of examples of the ‘proposed’ books (i.e. books in French about the Russian revolution) to facilitate further discussion;

- Remove content with Fraktur/Gothic script - but engaging with members for whom this affects outside of German Lit, e.g. philosophy; art theory;

Further discussion will be held with members later in 2020 about this area (see also the section on this in the summary of the drop-in sessions [insert link].)

Action: Collections Group to arrange further drop-ins on this theme for Summer or early Autumn 2020.

- Different editions:

Members also suggested that the Library carries out work on its holdings of different editions – i.e. move away from the Library’s traditional approach of holding different editions due to different prefaces, forewords, etc and reduce on-site holdings of multiple editions, particularly where these are extensive in authors such as Dickens and Shakespeare;

Action: Collections Group to investigate this further.

-Matthew Brooke, March 2020

Collection management update

December 2020

In 2019 the Library drew members’ attention to the new ‘Collection Capacity Management Strategy’, which is designed to better manage the space available within the Library to house our historic book collection and to allow the continued growth of new publications. As the next phase of this strategy, in the New Year we will move a selection of the periodicals held in the basement to off-site store. All titles to be moved are duplicated online and are available to members, either through the Library's subscriptions, such as JSTOR, or on open access websites, including Gallica and Biodiversity Heritage Library. Members will also be able to request print volumes of these periodicals through Catalyst, and they will be retrieved from the offsite store with two working days' notice.

A number of journals that are available online but which we know are well used in print at the Library will be retained on-site. The list of journals proposed for removal to off-site store is here. If there are any specific titles that members wish to retain on-site, please contact This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it..

Once the periodicals have been removed, a minor rearrangement of stock will be carried out and some additional temporary desk space will be made available whilst social distancing restrictions continue to reduce our available desks by a third.

Read more: Collection Capacity Management Strategy Implementation

Collection Management Drop-in Sessions January 9 and 14: Member Feedback

The proposed collection capacity management strategy is to withdraw from the collection some journal and government publication material that is available online; foreign language journal material that has ceased acquisition; obsolete material; and duplicate copies of books where these are not warranted. Additionally, the proposal is to begin a strategy to move some low-use books to off-site store, with selected foreign language works in subjects other than literature, history and art identified as a particularly low-use category with which to start.

The Library held 7 drop-in sessions which were attended by a total of 31 members. They produced a lot of lively discussion which will be extremely helpful to the Collections Team and the Collections Committee in considering how best to move forward through this very difficult task.

Key points raised by members are covered in the FAQs.

The points of the strategy which caused the greatest amount of discussion were around the nature and characteristics of the existing London Library collection, foreign language material, and communications with members. A summary of the feedback on these issues, and our responses to these, follows:

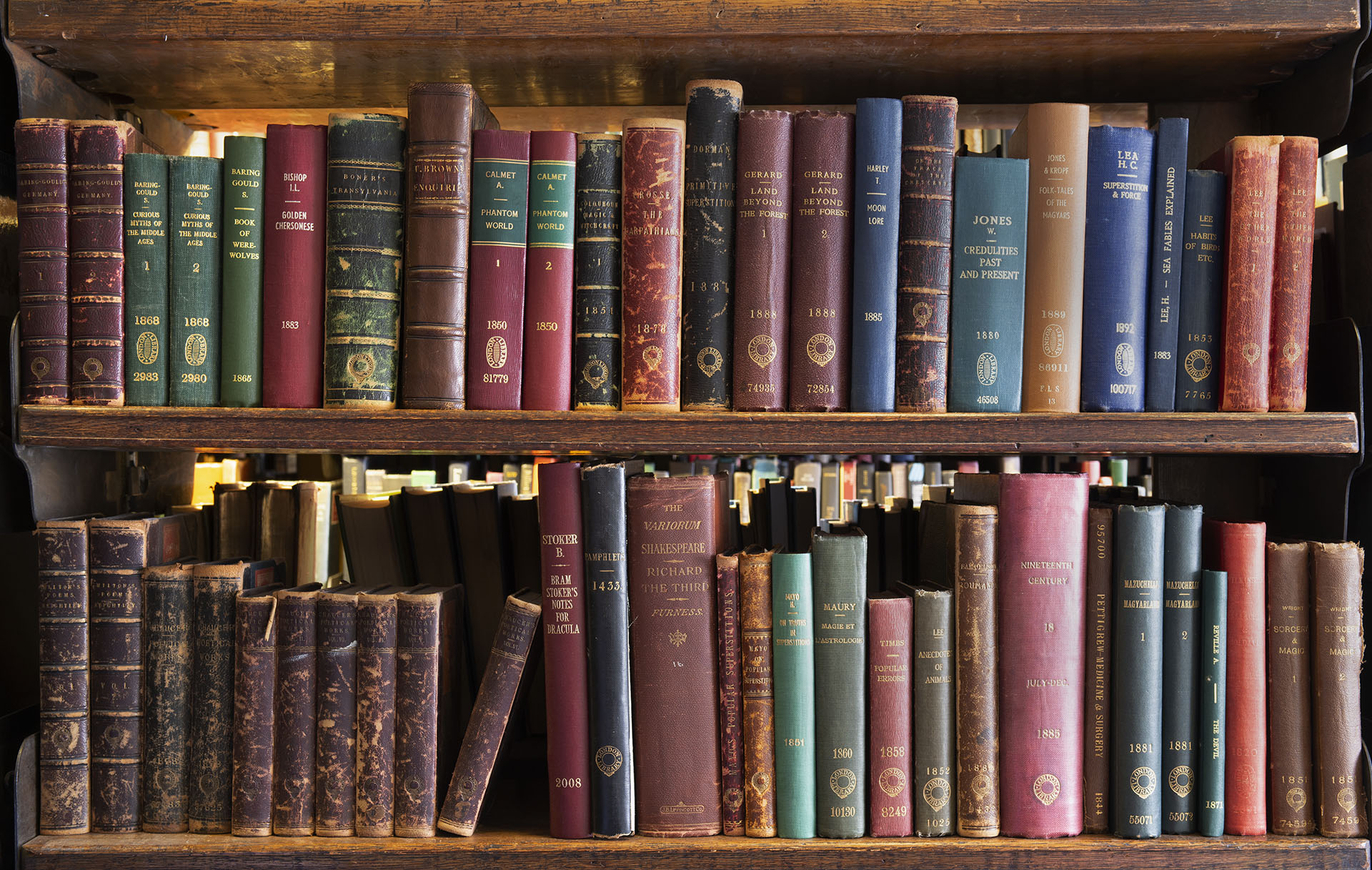

The nature of The London Library Collection

Members sought to ensure that the Library staff understood the attraction of the Library’s collection. Comments included the following points: that the eccentricity of the collection is a major reason for joining the Library, and we should be careful not to ‘throw the baby out with the bathwater’ and lose the quirkiness of the collection; that whilst librarians may have tidy minds, the eclectic mix to be found on the shelves is part of the Library’s unique value; that whilst there may well be a move towards electronic collection building, it is the extensive print collections that may be borrowed that are unique to The London Library; that many libraries no longer feel like places of scholarship, whilst The London Library has retained that atmosphere.

Response:

We have no desire or intention to erode the unique characteristics of the Library’s collection. Whilst we do believe that a greater reliance can be placed on electronic sources which duplicate extensive print holdings of periodicals and other long series such as government publications, we are fully appreciative of the breadth and depth of material that has been accrued over time and the uniqueness of the collection that we have. Our aim is therefore to handle the necessary reduction in stock held on-site with the utmost care, to ensure that the essential characteristics of the Library’s collection are not eroded.

Foreign language material

Members wished to ensure that the importance of the foreign language books was understood. Foreign language titles in Art, History and Philosophy, particularly nineteenth century editions, are important and to lose them would have implications for those researching the history of these subjects. There was a variety of viewpoints put forward, with one member suggesting that whilst he had borrowed eastern European books from the Library, the collection was not strong in some languages from that region so these could be candidates for withdrawal; it was acknowledged that German works in Fractur (gothic script) were almost illegible to most readers of German, but that removing this material would also impact upon the extent of some collections such as early art theory; the Russian literature collection is known to be strong by those who use it; poetry was given as an example of something which is arguably best read in the original language and it was felt that the Library ought to have better collections of poetry from other countries and cultures.

Response:

The feedback gained through discussions on foreign language material was extremely useful. This is an area where we will engage much more with members through further meetings to explore various options. The low circulation figures for foreign language material (of which there is a large amount) might make it a good candidate for off-site storage. However, this is merely a starting point for discussion, and further engagement with members over how to take such a matter forward will be arranged for later in 2020.

Communications with members

Members were keen to hear of any proposed plans before material is actually removed from the Library. There were requests to share as much information as possible about the Library’s collection management strategy, using more channels of communication and not just the e-newsletter; to let members know in advance what is planned to allow for feedback and safeguard against any assumptions being made about apparent low-usage of material that may be being consulted within the Library only; where possible, to post lists of material to be withdrawn or moved off-site on the website.

Response:

These drop-in sessions have been extremely useful, and are the very start of how we wish to engage with members over the ongoing collection strategy. There were articles in the Library magazine in 2019, as well as e-newsletter communications about government publications, but it does seem as though these are not reaching all members. We will endeavour to widen communications about our plans (for example, by creating these web-pages), and, as is mentioned above, engage in in-depth consultation with members through meetings where we feel we need detailed, qualitative input from members.